Seven Steps to Hurdle Heaven

Step Four: A Love for the Thing Itself

Many athletes don’t get past level three, the warrior stage. Ours is a level-three society. We idolize our warriors, our conquerors, whether they be on the field of battle, in the business world, or on the field of play. We study them, we analyze their strategies and methods, we strive to emulate them, we immortalize them.

We value winning. To lose is to fail. Losers are mocked, humiliated, criticized, or even worse, ignored. Losers are left to question if they wasted their time with all their hard work, if all the sacrifices they made proved to be pointless. They are left to wonder what more they could have done, what they could have done differently. If the goal was to be the best and I’m not the best, then I’m a failure.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

Winners are validated. Hard work pays off? Yes it does, and now I have proof. I won. I’m the best. The best in the county, the best in the region, the best in the state, the best in the nation, the best in the world.

The problem with being a warrior, and only a warrior, is that winning serves as the only validation for the work you put in. And as the saying goes, you can’t win ‘em all. Once you win once and feel that self-satisfaction, you have to keep winning in order to keep gaining that feeling. Once you’ve proven yourself, you have to keep proving yourself. Once you’ve fought your way to the top, you have to keep fighting to stay at the top. And after a while, you just get tired of it all. You get tired of training through injuries, you get tired of traveling to meets, you get tired of the deep waves of disappointment after bad races, you get tired of your coach preaching the same old yang-yang day after day. Mostly, you get tired of how your day-to-day emotional balance depends upon winning a race.

No matter how good you are, no matter how highly you are ranked, no matter how many races you’ve won, you’re going to reach a point where you start to think there has to be something more to all of this. For many, this thought nags them and may linger for a while, but it never becomes strong enough that they feel the need to act on it. Instead, they either continue on with the grind or they quit the sport. In both cases – those who keep grinding and those who walk away – they’ve given up on the idea that they could actually enjoy training and racing.

I’m reminded of a conversation I once had with a very successful, wealthy, famous novelist. Many of his books have been produced as blockbuster movies. He was talking about the writing process and how demanding it is to meet deadlines, sometimes requiring him to write several chapters of a book in the space of a week or two weeks. I remarked that it’s a good thing he loves to write, or else there’s no way he’d be able to write so much in such a short period of time. He looked at me with raised eyebrows and said, “I hate to write. Are you kidding me? I hate writing!”

I stuttered and stumbled for a response, totally caught off guard by his reaction, before I finally asked, “Then why do you write? Why do you put yourself through all of that stress if you don’t even like it?”

He threw his hands in the air like that was the stupidest question he’d ever heard. “Because of the challenge,” he said. He went on to explain what a rush he felt when he was hurrying to meet a deadline, hunkering down and pushing himself through fatigue, coming through on the other side with a gem of a story. He also enjoyed the financial rewards and the lavish lifestyle that his writing career provided him.

That is the Level Three mentality in a nutshell. The thrill of the challenge, and the external rewards that come with success, serve as the primary sources of motivation for working through the grind. And who would argue against the logic of such a mindset? If you hate what you do but you’re making bundles of money doing it, then suck it up and deal with it.

But not everybody is wired that way. For the Level Four hurdler, the idea that there must be “something more” to all this training and competing grows to be more than a nagging thought. It becomes a deep longing for an inwardly fulfilling experience. This longing, unbeknownst to the hurdler him/herself in most cases, is rooted in his or her beginnings as a hurdler, when hurdling was just “fun.” The fun is now gone, and the hurdler does not know how to get it back. He or she even suppresses thoughts of wanting to get back to it because he or she has been taught – by coaches, teammates, and society at large – that the path to greatness is not supposed to be fun. It’s supposed to be work. And once you become a serious, dedicated athlete, you should outgrow the need for fun.

But “fun” is too small of a word. “Love” would be more appropriate. About three years ago I wrote an article for this website entitled “The Love Factor.” In that article I argued that when an athlete is motivated by love – love of the hurdles in this case – that love leads to higher levels of performance and to greater peace of mind. When you love what you do, you put all of yourself into it. Not because you’re compelled to, not because there’s a reward awaiting you at the end, but because the experience itself is enjoyable.

As that article explains, the Level Four hurdler comes to realize that there is, in fact, something more beyond the winning and the losing, the time on a stopwatch, rankings and seedings, medals and ribbons and money and fame. Beneath all of that, quietly waiting to be re-discovered, there is hurdling, in its purest form, unattached to any desires. The Level Four hurdler come to this realization on his or her own, and though he or she may resist it at first, he or she will eventually surrender to it, at which point a subtle but major transformation occurs.

The Level Four hurdler does not stop being a warrior; in fact, he or she becomes an even better-equipped one. He or she has a clarity of mind and calmness of spirit that wasn’t there before, when his or her sense of self-worth hinged on the result. There is far less chance that he or she will sabotage his or her own efforts with negative thoughts.

In a recent conversation with one of my former athletes, he was talking to me about his first year of competing at the collegiate level. Specializing in the 400 hurdles, he’d been having a good season, had dropped time from his high school personal best, and was close to qualifying for the IC4A meet. The chance to make IC4A’s as a freshman really excited him, and he found himself growing more tense in the days leading up to the last meet that would give him a chance to qualify. As he warmed up for his race and did a run-out over the first hurdle, he pumped himself up with a lot of You can do this! chatter. But right before he stepped into the blocks to run the race, he realized that his attempts to pump himself up were just making him more nervous. “That’s when I reminded myself,” he told me, “that I’m doing this because I love to do it. I love running the hurdles.” He went on to explain that with his mind free of the pressure of hopes and expectations, he ran another personal best and qualified.

The point is clear. A lot of people assume that “doing it for the love” means that you don’t care if you win or lose, that you’re content to just “do your best.” That’s not the case. It’s not so much that you don’t care about winning, but that you don’t judge yourself – as an athlete nor as a person – based on whether you win. Paradoxically, as my former athlete expressed, the less you obsess over winning, the more you improve your chances of winning. Or specifically in his case, the less you obsess over qualifying for a big meet, the more you improve your chances of qualifying for the meet. Focusing on the love releases tension, which allows you to be fully present in the moment, to be in total control of your body’s movements, totally silent in regards to mental noise, totally capable of making split-second adjustments to rhythm and speed throughout the race.

In essence, the Level Four hurdler is a higher-level warrior. Where the Level Three hurdler conquers fear as one conquers an enemy, the level four hurdler sheds himself of fear, recognizing it for the illusion that it is. Where the Level Three hurdler sets out to conquer his opponents and prove his superiority, the Level Four hurdler is focused solely on running a well-executed race, fully confident that doing so will lead to positive results.

I remember reading somewhere that sprinting, and for our purposes hurdling, is all about letting go of inhibitions. The difficulty though, according to the author, is that you don’t know you have inhibitions until you let them go. Along those lines, the difference between the Level Three hurdler and the Level Four hurdler is that the Level Three hurdler doesn’t realize he still has inhibitions. He still believes that he needs to keep “fighting” to get better, that he needs to “push” himself more. The only thing the Level Three hurdler knows how to do is work harder, to do more – more reps over hurdles, more reps in the weight room, more push-ups, more lunges, more more more. This attitude increases tension, increases self-doubt, and creates feelings of guilt and inferiority. You assume that everyone who is beating you, everyone who is running faster than you, must be working harder than you.

The Level Four hurdler has let go of such inhibitions. He doesn’t judge himself. He doesn’t feel superior when he wins; he doesn’t feel inferior when he loses. He remains humble in the face of victory; he remains confident in the face of defeat. His hard work isn’t attached to results. He works hard because the work doesn’t feel like work at all. He sees training as a creative process, as a chance to master an art form that continually invigorates him and teaches him valuable lessons that he can apply to all aspects of his life. He loves hurdling. He loves how he feels when he is hurdling. He loves who he is when he is hurdling. This love is the primary source of his motivation.

Both the Level Three hurdler and the Level Four hurdler are willing to take risks, to experiment, but for different reasons. The attitude of the Level Three hurdler is, if it’ll help me run faster, I’ll try it; if it’ll make me better, I’ll do it. And the Level Three hurdler doesn’t want to learn something new in steps; he wants to learn it all at once. The attitude is, Show me how to do it so I can use it in my meet this weekend.

Meanwhile, the Level Four hurdler is guided by the same natural curiosity that led him to try hurdling to begin with. For the Level Four hurdler, the whole point of training is to learn new ideas, to try new technical approaches, and to experiment with a variety of training methods. He never loses the spirit of adventure, the spirit of play, even at the highest levels of competition. Practice never consists of “the same old thing.”

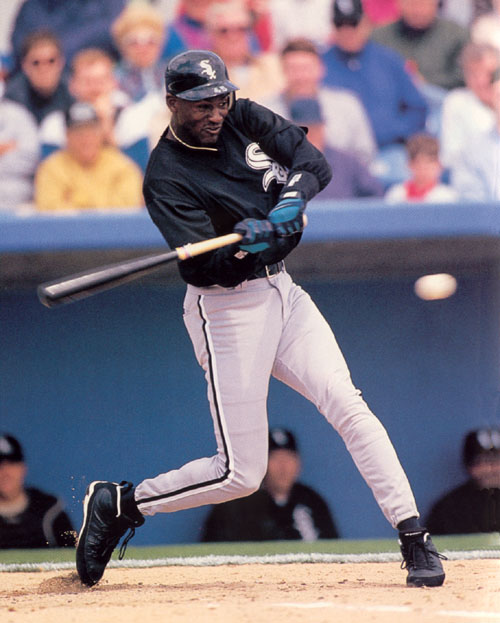

A realization of the love can be triggered sometimes in the Level Three athlete by great success, when victory and glory don’t lead to the elation the athlete was expecting. Let me go outside of track and field for my example. When Michael Jordan quit the NBA to try his hand at minor league baseball after winning three consecutive championships with the Chicago Bulls from 1991-93, everyone either thought he was crazy or they were coming up with conspiracy theories to explain this seemingly inexplicable decision. He was King of the World. The Bulls had many more years of NBA titles ahead of them. Why retire now? In the prime of his career?

The answer is simple: he had lost the love. And despite, all the success he’d achieved he couldn’t hide that fact from himself. He couldn’t lie to himself. Success and fame had become a trap. He’d achieved all the glory the sport had to offer and still felt empty inside. The tragic death of his father shortly after the third championship made him question his own motivations for continuing on, and made him long for the love of play that he had known as a child. And because baseball was the sport his dad had first introduced him to, and because he hadn’t competed in baseball at nearly as high a level, taking a shot at making a minor league team represented an opportunity to return to doing something he loved to do simply because he loved to do it. Back to the essence, back to the purity. Damn what the world thinks.

Then a funny thing happened. While he was playing baseball, he realized that he did love basketball. The love had been clouded by fame and fortune, maintaining a public image, being idolized, and carrying the weight of the whole league on his shoulders. But when away from the sport, he missed it. When he could look at it from a distance, with some perspective, he realized that his love of the game was real, that it had survived ten years of NBA rigors, that it had survived brutal playoff battles against the Detroit Pistons, that it had survived relentless scrutiny as an adored pop icon, that it had survived even the death of his father. He had thought that it would be fitting to say that his dad had been there to see him play his last game. He had thought that with three rings and millions of dollars, walking away and staying away wouldn’t be so hard. But he discovered otherwise. The game pulled him back, perhaps even against his own will. That’s why he started hanging out at the Bulls’ practice facility in the latter part of the ’94-95 season. That’s why he started taking part in team scrimmages. That’s why he came back.

Through many of the profiles I’ve written over the years – for this magazine, and for this website prior to the magazine’s inception – it has become quite clear to me that many elite hurdlers are motivated by a love for hurdling more so than by any other factor. Renaldo Nehemiah spoke of it extensively. The subject came up in interviews with the likes of Ron Bramlett, David Oliver, Dominique Arnold, Antwon Hicks, David Payne, Kim Batten, Kevin Young, Shelia Burrell, and many others. All of these hurdlers are very profound thinkers who look upon hurdling as their craft, as the number one thing in the world they prefer to do, not just as a means to make a living. In an interview with Ato Boldon earlier this year, Allen Johnson stated that he considered hurdling to be “like going outside to play.” Boldon had asked a question about why Johnson stuck around so long, well into his late 30’s, and Johnson was explaining that he stuck around because he loved to hurdle.

Boldon’s interview with Johnson. Jump to the 2:00 mark for Johnson’s comment about hurdling being play.

Terry Reese, the profile subject for the October 2013 issue of this magazine, serves as a great example of someone who visibly demonstrates what someone who loves to hurdle looks like. At age 47 he continues to do hurdle workouts on a regular basis, and can still clear 42-inch barriers with no problem. He’s not training for any races, he’s not planning to compete in any masters’ meets. As with Johnson, the track is his playground.

And that’s how it is for those who have the love; they don’t need a reason to hurdle. They don’t need to prove anything to anyone, they don’t need to accomplish any goals. The love for the thing itself is enough.

***

My plan is to discuss Steps 5 and 6 of the Seven Steps to Hurdle Heaven in next month’s issue. I had planned on getting to Step 5 in this issue, but Step 4 went on a bit longer than I thought. Same thing could happen with Step 5; we’ll see!

[/am4show]