The Eighth Hurdle

While no part of a 400 meter hurdle race is inherently more important than any other, I would argue that a key trouble spot that can make or break a race is hurdle number eight. The approach to this hurdle, the clearance of it, and the run off of it, can mean the difference between glory and disaster. In this article I will address why I feel that to be the case, and discuss ways to deal with the issues that come up at this stage of the race.

Let’s start with the mental aspects first. Hurdlers don’t like hurdling on the curve. It’s unnatural, it’s awkward, it feels funny, it can throw off your rhythm and timing, you’re more prone to landing off-balance, there’s a greater danger of illegally hooking a hurdle, and it’s simply not as fun as hurdling on the straight-away where it feels like you can run downhill all day long.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

So with the eighth hurdle being the last hurdle on the curve, it’s a hurdle where hurdlers grow impatient. Their mind turns to the homestretch as they grow eager to make up ground, surge ahead, push to the finish line. When the mind is in that eager, anticipatory state, it is more prone to causing mistakes. Before you can focus on the homestretch, you have to clear the hurdle. Focusing on the homestretch too soon can lead to poor execution and a breakdown in timing. I like to compare it to a wide receiver in football. The ball’s coming at you, and you see daylight ahead. A chance to bolt past the defensive back and sprint into the open field toward the end zone. But you’ve got to catch the ball first. How many times has a wide receiver dropped an easy pass because he took his eye off the ball, so eager to dash into daylight? Happens all the time.

Similarly, for a 400 meter hurdler, the homestretch is that daylight, and the eighth hurdle must be cleared efficiently before making that final sprint home. When there are opponents on either side of you – some of whom you’re chasing down, some of whom are chasing you – it’s not easy to stay disciplined mentally and keep your focus on the hurdle. The hurdles are now side by side, and arms and elbows are flying. But you have to clear the hurdle, and land on the other side, before you can attack hurdle nine.

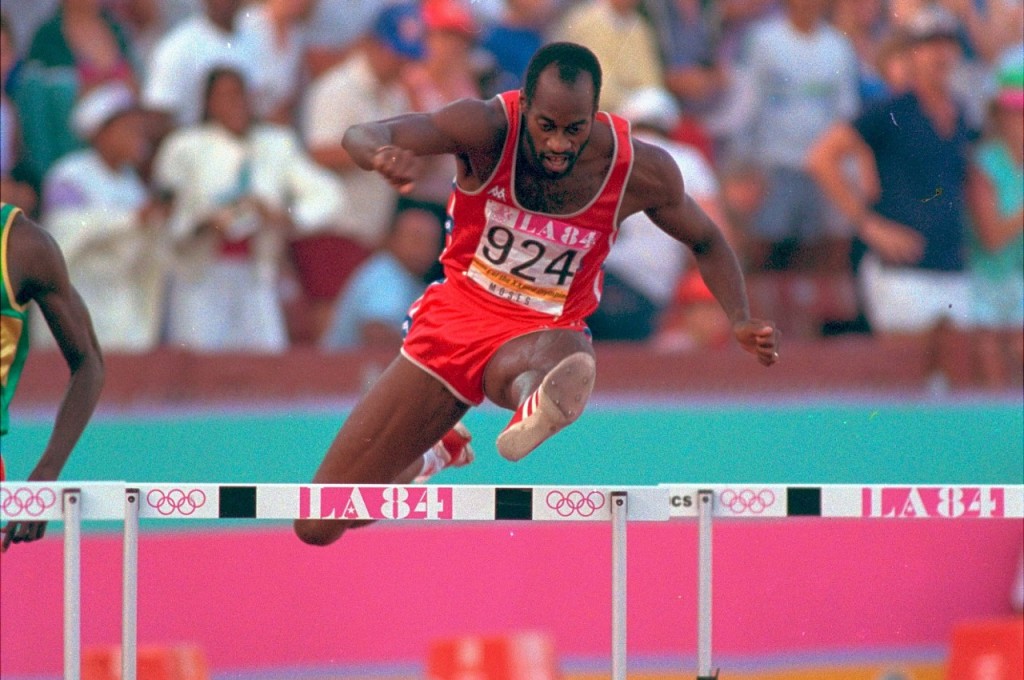

Edwin Moses clears the eighth hurdle at the 1984 Olympics (photo courtesy hereandnow.wbur.org)

Another reason that the eighth hurdle can be troublesome is because of the level of fatigue that has set in by that point of the race. You’re on the curve, and you’re tired. So you’re very susceptible to a breakdown. If you don’t employ a consistent stride pattern (the same amount of strides between the hurdles all the way around the track), then this hurdle can potentially present even more danger, because it’s a decision hurdle. Meaning, it’s a hurdle you’re going to have to make a decision regarding which leg to lead with. You don’t want to stutter into it, and you don’t want to reach for it; either way, you’ll suffer a major loss of speed and momentum, and you’ll feel the breeze of your competitors flying past you.

Let’s say, for example, it’s a big meet, you’re really amped up, and your plan going into the race was to take 13 strides through hurdle five, 14 through six and seven, and 15 through eight to ten. But as you transition off hurdle seven into hurdle eight, you’re feeling like you can 14-step it. If you go for it, you’ll be clearing the hurdle with your weaker lead leg, but you’ll be able to more easily keep the rhythm that you’ve already established. If you try to stick to the plan and go with 15, you might get crowded and be forced to chop your steps.

Of course, this type of scenario can come up at any hurdle past the midway point of the race, but I feel it is most dangerous at hurdle eight because of the combination of fatigue and the end of the curve. At hurdles nine and ten, fatigue continues to be a major factor, but being on the straight makes it easier to recover from a loss of balance. And I also feel that if hurdle eight is cleared fluidly, with good momentum, then that momentum can be carried over the last two hurdles and through the finish line with relatively little trouble. But more on that a little later.

My feeling about planning out a stride pattern, except for those hurdlers who employ a consistent stride pattern, is to use the plan as a guide, not as a rule. In the heat of the moment, you have to go with what you feel. Ultimately, it’s not really about making a decision regarding how many strides to take. More so, it’s a matter of keeping the rhythm and maintaining efficiency, and trusting the leg that comes up, even if it’s the weaker one. My advice for maintaining a rhythm is simple: keep the hands high. Keep that cheek-to-cheek motion with the arms. Don’t drop the hands in an attempt to time your take-off into the barrier. If the hands drop, the knees will drop, the chest will sink in, and you’ll be stuttering like a tap dancer. Nor should you raise the hands too high in an attempt to reach for the hurdle. Nothing can kill momentum like overextending your stride and taking off too far away from the obstacle, especially at hurdle eight.

In an article I wrote for this website eight years ago, “Consistent Stride Pattern,” I advocated for developing a consistent stride pattern. And hurdle eight is one of the most important moments in a race where being able to run without thinking really does help. If you know, for example, that you take 15 strides between the hurdles all the way around the track, then the issues caused by fatigue will be minimized. There’ll be no stuttering and they’ll be no over-extending. To me, that’s one of the things that made Edwin Moses so special, and so consistent. He always went into a race knowing what he was doing. There was never any guess work involved. Thirteen all the way around. Let’s get it.

As for hurdles nine and ten, as long as you’re in the type of physical condition needed to meet the demands of the event, you should be able to attack those two hurdles aggressively if you come off hurdle eight and into the homestretch with good speed, balance, and momentum. The worst is over, so to speak. Now the challenge becomes even more mental, as you must manage to relax, maintain your angles (hand height and knee height), keep applying force to the track, all while the hurdles keep coming at you and the chase for the finish line becomes frenzied.

Americans Johnny Dutch and Jeshua Anderson clear the eighth hurdle at the 2008 World Junior Championships (photo courtesy Zimbio.com).

Americans Johnny Dutch and Jeshua Anderson clear the eighth hurdle at the 2008 World Junior Championships (photo courtesy Zimbio.com).

But in a lot of ways, hurdle eight sets up the rest of the race. The 400 hurdles is all about energy distribution. And when it comes to the 400 hurdles, the later you are in the race, the more costly a mistake is, for the simple fact that you’re too tired to recover from it. And when I say “mistake,” I’m talking about rhythm mistakes – stuttering or over-extending, not technique mistakes. I’ve seen plenty of hurdlers hit hurdles nine or ten but still finish the race strong because they had plenty of forward momentum going into the hurdle. When Kevin Young ran his 46.78 at the ’92 Olympics, he smashed the last hurdle with his lead leg but just kept right on rolling to the finish line. So my point is, if you are able to attack hurdle eight with aggression, you should be able to do the same over the next two and through the line.

For hurdlers who are transitioning from high school to college (or high school hurdlers who run the 300 hurdles during the school season and the 400 hurdles in youth track), hurdle eight represents an enormous psychological barrier. The body wants to stop because it’s used to the race being over at that point. That issue can only be addressed in training, and by getting experience running the longer race.

For high school hurdlers running the 300 hurdles exclusively, hurdle five would be the hurdle where the points made in this article would be relevant. But in the 300’s, fatigue should not be the factor that it is in the longer race.

In practice, it’s important to create workouts that will address hurdle eight issues. Here are a couple ideas:

Do some reps that focus strictly on the second curve. For example, start at the 200 start or the mark for the fifth hurdle, and sprint over hurdles six through eight. Put a cone to serve as a finish line about 10 meters beyond hurdle eight. Such a workout will give you a feel for managing the curve, attacking hurdle eight, and running off it.

To mimic the fatigue that you’ll feel at hurdle eight, something like this might work: Starting at the 400 meter start line, run a full speed 200 with no hurdles; take a 1:00 rest, then run another 200 over last 5 hurdles. Two or three sets of that should be sufficiently exhausting and will force you to address the issues that you will face in a race.

[/am4show]