Groin Strains

Groin strains are most commonly associated with sports that require quick, sudden shifts in direction, such as soccer, lacrosse, hockey, football, and basketball. But groin strains are also very common in track and field, particularly among jumpers, sprinters, and hurdlers – events that require little to no lateral movement. While shin splints and hamstring strains plague hurdlers most frequently, groin strains are also high on the list of hurdlers’ banes. The reason that groin strains occur in hurdlers (and sprinters and jumpers) despite the lack of lateral movement is because of the high knee lift required in these events, and also because of weaknesses in nearby muscle groups.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

Like other injuries common to hurdlers (such as the ones mentioned above), groin strains are largely an overuse injury. For the lead leg, the action of leading with the knee is the culprit; for the trail leg, the action of rotating the knee to the front is the culprit. Even if your mechanics are sound, the repetition of the movements over and over again in drills, workouts, and races can lead to groin strains. Still, with that being the case, my observation has been that, for hurdlers, groin strains most commonly occur in the trail leg – particularly in the trail legs of hurdlers who have faulty trail leg mechanics.

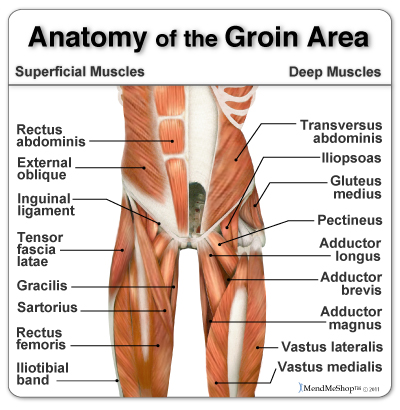

Before getting too far into the discussion, let’s go ahead and define what the “groin” actually is, and how it functions. According to podiatrist and track coach Kelsey Armstrong – my reliable source for all things medically related – the groin is a “catch-all term referring to five muscles in the inside of the thigh: the pectineus, adductor brevis, gracilis, adductor magnus, and adductor longus.” The main function of these muscles is to “bring the leg toward the midline of the body,” which is known as adduction.

The groin muscles function in conjunction with other core muscle groups, namely the hip flexors and the gluteal muscles. Weaknesses or an overworked condition in either or both of these areas can force the groin muscles to function in ways they weren’t necessarily meant to, leading to strains. Armstrong states, “injuries to [the groin] muscles are usually due to these muscles doing more than they can handle, as a large component of their activity is postural in nature. This excessive activity is due to muscular imbalances and faulty body positioning elsewhere.”

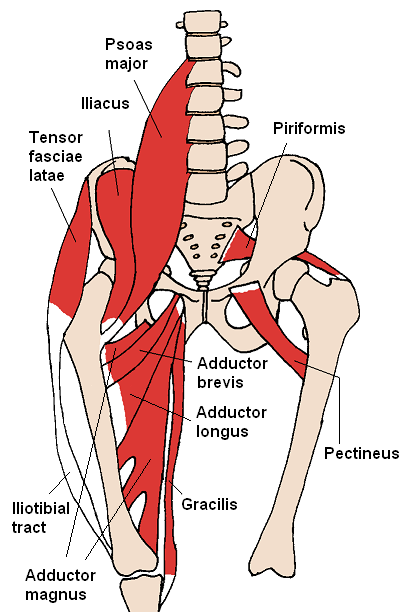

The muscle group that is most prone to overuse, thereby indirectly leading to groin strains, is the hip flexors. Sprinters and hurdlers, due to the nature of their events, are prone to having tight hip flexors. “This is created by repeated sprinting activity,” Dr. Armstrong says, “which emphasizes high knee lift, the slight forward lean of sprinting (especially hurdling) and the increased postural component when the leg is on the ground during sprinting.”

The iliopsoas muscle group of the hip flexors does the bulk of the heavy lifting for sprinters and hurdlers. That’s why it’s the group that becomes tight. Meanwhile, two of the groin muscles – “the pectineus, and to a lesser extent, the adductor brevis – have a lesser function as hip flexors also.” So when the muscles of the iliopsoas group tighten up, the pectineus and adductor brevis take on a greater role as hip flexors. As a result, “these muscle groups are prone to become overworked due to their increased duty, making them liable to injury.”

Getting back to the point made in the beginning of this article about sports that require constant shifts in direction, I would say that this element exists for the hurdler in regards to the trail leg. To clear a hurdle, the groin of the trail leg must open up before driving the knee to the front. This motion is unnatural and must be taught and mastered through drills. It’s not unusual for most beginning hurdlers to bring the trail leg through directly under the butt, without opening the groin at all. This method of hurdling is highly inefficient and very dangerous, potentially leading to face-first crash landings. So proper trail leg form must be taught early on.

The reason many hurdlers are susceptible to groin strains is because they either open their groin too widely, or because they have back-kick in their running stride that causes the groin to twist after the trail leg pushes off, or because the knee of the trail leg points outward (to the left for the left leg trail leg, to the right for the right leg trail leg) during hurdle clearance instead of facing forward.

Such flaws in mechanics, repeated over and over again, can easily lead to groin strains. When I was competing, my groin on the trail leg side was always sore, mainly because I kept it too low and brought it around too late. Whenever I drove it to the front I could feel it yanking, until finally I taught myself to raise it higher immediately after take-off, which solved the problem.

To prevent groin strains on the trail leg side, I think it’s important to do the old-school, basic fence drill on a daily basis. If you’re not familiar with the drill, all it consists of is setting up one hurdle facing a fence (or wall if you’re inside), with about a yard of space between the fence and the crossbar. Stand beside the hurdle with your hands on the fence. With the foot of the lead leg planted firmly on the ground, repeatedly cycle the trail leg over the crossbar in a series of reps. From the ground to the ground is one rep.

This drill serves multiple purposes. First, it serves as a way for the beginner (and the experienced hurdler with bad habits) to ingrain proper trail leg technique. Coaches must monitor this drill closely to make sure the athletes are doing it properly – with the ankle dorsi-flexed, the groin opening only as much as needed to clear the hurdle, with the knee rising, and with the knee always facing the front. Learning proper trail leg mechanics early not only makes for better hurdling, but also reduces the chances of injury, particularly to the groin muscles.

In the above video, Coach Shelia Burrell has one of her athletes demonstrate walk-overs and the fence drill.

Secondly, this drill strengthens all the muscles on the trail leg that need to be strong – the hip flexors, the glutes, and the groin. Not to mention the lower back. I’ve sometimes had athletes do this drill with an ankle weight on – one in the range of 2-5 lbs. Heavy enough to help increase strength but not so heavy to cause a strain. Usually I incorporate it into the warm-up. A total of 100 reps per day is all you need to reap the necessary benefits.

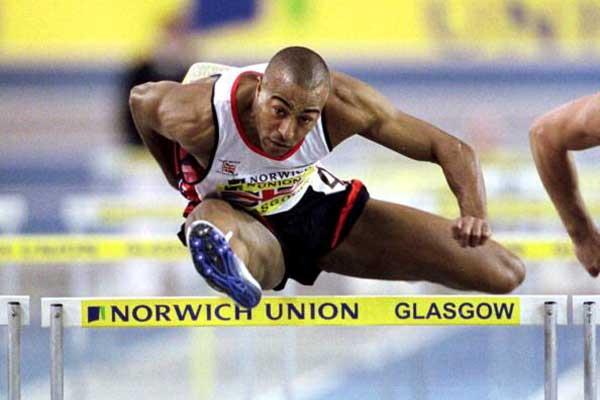

Another way to prevent groin injuries is to start low and start slow – whether you’re talking about a beginning hurdler just learning or an experienced hurdler at the start of a new season. The more you can ingrain good mechanics at lower heights, the easier it will be to do so at higher heights, thus reducing the risk of injury. Even with efficient mechanics, I think it’s safe to say that the higher the hurdlers are, the greater the risk of injury, as you will need to put your body into positions that are difficult to achieve, much less master. For a male hurdler going over a 42-inch hurdle, the amount of strength and flexibility needed in the groin and hip flexors is comparable to that of a pole vaulter or gymnast.

Former World Record Holder Colin Jackson demonstrates why hurdling requires so much strength and flexibility in the hip flexor and groin muscle groups.

Hip opening exercises, such as walk-overs and over-and-unders with hurdles, can also serve to strengthen and increase flexibility in the hip flexors and groin muscles. Incorporating them into your warm-up a few days a week would be a good idea.

Dr. Armstrong says that treatment for groin strains is the same as for a strain or tear in any other muscle group – rest, ice, compression, elevation. No, icing your groin isn’t fun, but you gotta do what you gotta do. When coming back from a groin injury, don’t come back too soon, and don’t go too hard too soon. The last thing you want to do is re-aggravate the injury and have the injury linger throughout the season.

Besides the RICE treatment, Armstrong says that the best treatment is prevention – “not forcing these muscles to be overworked.” That could mean, during a dynamic warm-up, sitting out any stretches or skip drills that require a significant range of motion. It could also mean hurdling at race height as infrequently as possible.

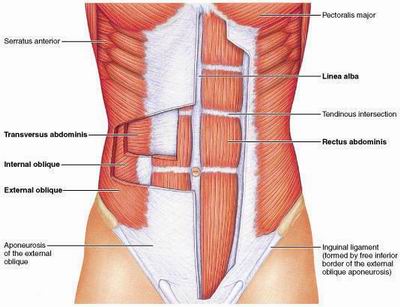

In addition, Armstrong suggests that “hip flexor stretching along with soft tissue release can help with the tight iliopsoas muscles, along with a de-emphasis on extreme high knee exercises. Abdominal exercises will help tilt the pelvis properly (the ones that target the internal and external obliques and transverse abdominis – the regular crunches work the rectus abdominis and are not recommended). Lastly, exercises that focus on the gluteal muscles will help it to regain some of its strength, i.e., Deadlift, Romanian Deadlifts and Hip Thrusts.”

On the whole, the greatest lesson I learned from Dr. Armstrong’s insights is that it is important for coaches and athletes to be aware of how much the different muscle groups relate to each other. That doesn’t mean you have to know all the Latin terms for each muscle group, but it does mean when you feel a twinge in your groin, you better do your hip-opening exercises and oblique work. Don’t just ice your groin and think you’ll be all right.

Track is an unforgiving sport to the injured athlete. If you’re not competing at 100%, you’re at a significant disadvantage, and no one feels sorry for you. That’s why, when it comes to groin strains or any other type of injury, you must listen to your body’s warning signals and limit, reduce, or entirely cut out any movements that can lead to long-term debilitation.

[/am4show]