Dealing with Achilles Tendonitis

Another injury that can be added to the list of those that plague hurdlers would be Achilles tendonitis, a chronic condition in which the Achilles tendon constantly feels sore, achy, and stiff. As with hamstring strains and shin splints, Achilles tendonitis is an overuse injury for hurdlers usually caused by clearing hurdles over and over again in practice sessions and in races through the course of a season. This article will discuss ways to prevent Achilles tendonitis, ways to treat it, and how to recover from a full-blown Achilles tear.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

Okay, so first of all, what is the Achilles tendon? According to The Hurdle Magazine’s injury expert, Dr. Kelsey Armstrong, “the Achilles tendon is made up of two muscles, the gastrocnemius and soleus. The gastrocnemius is the most prominent muscle that you can visibly see, and it crosses the knee and ankle joints as a tendon. The soleus muscle, which is less visible, only crosses the ankle joint as the Achilles tendon. Their function is based on their location in the body. Both of them can plantarflex (point the toes) the ankle, but the gastrocnemius is less efficient because it can bend the knee. The soleus can function irregardless of the knee’s position.”

Armstrong notes that, “during running activity, especially sprinting, these two muscles are lengthened (“pretensed”) during knee lift and foot contact, and begin to contract as the body comes over the planted foot, with the greatest activity during toe-off.” So the constant repetition of lengthening and contracting can put strain on the Achilles over a period of time. If this is the case for sprinters, it is even more true for hurdlers. To clear hurdles, the lengthening during knee lift is extended, and the contraction during toe-off is intensified.

Armstrong notes that, “during running activity, especially sprinting, these two muscles are lengthened (“pretensed”) during knee lift and foot contact, and begin to contract as the body comes over the planted foot, with the greatest activity during toe-off.” So the constant repetition of lengthening and contracting can put strain on the Achilles over a period of time. If this is the case for sprinters, it is even more true for hurdlers. To clear hurdles, the lengthening during knee lift is extended, and the contraction during toe-off is intensified.

So, unlike with other hurdling-related injuries (such as hamstring strains and groin strains), proper mechanics do not ensure a reduced risk of injury. You can be doing everything right in regards to your mechanics and still be susceptible to Achilles tendonitis. This fact was made painfully clear in the 2012 Olympic Games, when Liu Xiang, arguably the best technician in history, couldn’t clear the first hurdle of his preliminary round due to extreme soreness in his Achilles. In that race, Liu hit the first hurdle with his lead leg and crashed to the ground. To the untrained eye, it looked like he just got too close to the hurdle. But he was on his way to the ground before he even took off. Andrew Das of The New York Times wrote that Liu’s “ left foot hit the hurdle squarely because he was unable to generate enough spring with his right.”

Liu would soon thereafter have surgery for his ruptured Achilles, and he hasn’t been the same since.

Probably the most famous case of a ruptured Achilles in recent sports history would be that of Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant, who tore his Achilles while pivoting to change direction while making a move to the basket in a game against the Golden State Warriors. Kobe heard something “pop” and thought the player defending him had kicked him. Sadomasochist that he is, he got up and hit two free throws before heading to the locker room for an evaluation.

In the cases of both Liu and of Bryant, there was overuse leading up to the injury that made the injury inevitable. In the case of Liu, he had been preparing for the Games furiously, hoping to redeem himself after enduring very similar circumstances in the 2008 Olympics due to an ankle injury. He had raced very fast earlier in the season, including a windy 12.87 at the Prefontaine Classic earlier that summer. But, probably because of the previous injury, which took him a few years to return from fully, the Achilles was vulnerable, and the fast races he ran may have done some damage. In the case of Bryant, he had been playing through multiple injuries throughout that season, had been logging way more minutes that a man his age should have been logging, until finally his Achilles just literally snapped.

So, to avoid the tear, which can be career-threatening, proper care must be taken when Achilles pain is in its earlier stages. First off, it’s important, when beginning fall training, to ease back into the flow. Don’t start by spiking up and doing 150m repeats all-out. Start with slower, lower-impact training that won’t put so much strain on the lower legs. As with shin splints, one of the best ways to keep Achilles tendonitis at bay is to practice as often as possible in flats. Back in my day, we only wore spikes when we were practicing our block starts. But nowadays athletes want to spike up every day. That’s impractical for the year-round track athlete. Spikes are for running fast, not for the grind of everyday training.

Once the base training of the fall season has been completed, it’s important to continue to gradually increase speed and intensity. According to Dr. Armstrong, “Achilles tendonitis will occur when the forces placed on the tendon exceed its capacity. This happens during a sudden change of training intensity, introduction of hill running or speed work, and returning to training after a period of rest or an inadequate period of rest. The forces can also be increased on the support leg during activities that have increased duration on one leg (i.e. hurdling). The forces are also increased in high arched and low arched feet, albeit in different ways.”

The “support leg” for a hurdler, obviously, would be the trail leg. My observation has been that most Achilles injuries for hurdlers do occur in the trail leg, as it is the leg that pushes off and extends. However, because the lead leg has to endure the impact upon landing, Achilles tendonitis is not uncommon in the lead leg as well.

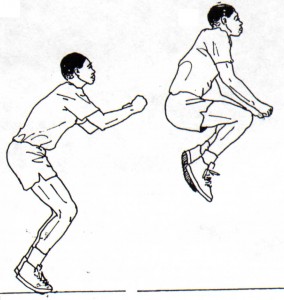

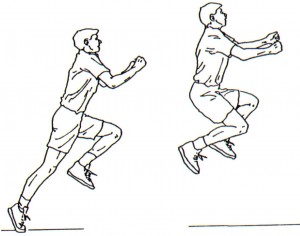

As for recovery from an inflamed Achilles, some time off from impact-related training comes first. Dr. Armstrong says that “it usually takes about three to five days for a normal tendon to recover from injury. Therefore, the stress of the Achilles tendon must be reduced in order for the tendon to recover adequately. Recovery activities include, in order, stretching, heel lifts, isometric exercises, toe raises (double leg first, then single leg), short two-legged jumps, single-leg hops, explosive hops, skipping, then finally running.”

The Achilles wall stretch is very similar to the calf stretch. The difference is that, to stretch the Achilles, the knee of the back leg will bend until the stretch is felt. In the calf stretch, the knee remains locked.

To stretch the Achilles on stairs, place the front part of the feet on the stair, with the back part of the feet hanging over the edge. Bend the knees slightly, and you will feel the Achilles stretch.

Hurdlers shouldn’t run over hurdles again until they’ve been able to hop and sprint pain-free. Then hurdling should be introduced slowly, starting with drills at lower heights before building up to race height and race speed.

***

Sources (other than the Kelsey Armstrong Interview):

http://www.sprintic.com/injuries/achilles_tendon_description/

http://wagesofwins.com/2013/04/19/the-curious-case-of-kobes-achilles/

http://www.footlogics.com.au/achilles-tendonitis-pain-treatment.html

http://www.athleticadvisor.com/weight_room/hops.htm

[/am4show]