Ken Stone: No Mere Muggle

About nine years ago I was writing a book on 1972 Olympic high hurdle champion Rodney Milburn when Ken Stone, copy editor for The San Diego Union-Tribune and webmaster of www.masterstrack.com, emailed me and offered to proofread and edit the beginning chapters in hopes of helping me find a suitable publisher. He loved the first chapter and raved about my writing style. But the second chapter came back to me filled with comments, suggestions, and crossed-out lines. After editing the chapter per his feedback, it dwindled down from its original length of over 11,000 words to being slightly above 8,000. After reading my revised version, he sent it back to me again with a note at the top reading, “Now the real editing begins.”

I was starting to feel incompetent. I had chopped off 3,000 words yet he was still pointing out places where I could pare things down. No word was safe. He had me taking out the’s and a’s if the sentence made sense without them. Despite my wounded pride, I followed all of his suggestions, leaving the word count for the third draft somewhere in the 6,000 range. Finally he emailed me back saying, “Good job.”

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

I went back and reread the third draft, and then went back and reread the first one. What I discovered shocked me: I had almost literally cut the chapter in half – from 11,000 words to 6,000 – yet I had lost nothing of value. And the final draft flowed a hundred times better than the first. The wordiness of the first draft – the overdramatization, the excessive buildup to key scenes, the overexplaining of things the reader could easily figure out through context – made me cringe to admit I had written it.

That’s when I realized that for all of his good-natured sense of humor and zest for life, Ken Stone, at his core, was a man who didn’t put up with sloppy work. Any inefficiencies needed to be addressed directly and corrected immediately. That’s probably a lesson he learned from his long career as a hurdler – one that started his freshman year of high school and goes on to this day at age 59.

Born in Detroit, MI, on June 18, 1954, Stone was raised in the nearby suburb of Oak Park until the age of 8, when his family moved to Orange County, CA. He lived there until the age of 16, when his family moved again, this time to Omaha, NE.

Known mainly as the webmaster of the masters track site, Stone has done more than any other single individual to promote the credibility of masters track among those who follow track and field in the United States, and throughout the world. He started the website back in February1996 as a weekly hobby, and it soon became a known entity around the world. These days, the site gets 40,000 unique visitors each month, and Stone has written well over 4,000 blog posts.

Besides the writing, Stone walks the walk of a masters athlete. He has competed in masters track since the age of 41, has attended USA outdoor masters nationals 13 times, and has competed in three World Masters Athletics championships, occasionally winning a medal. Besides hurdles, he has competed in high jump and sprints.

Stone was a copy editor at San Diego’s major daily newspapers from 1986 to 2003, when he joined the merged paper’s website, SignOnSanDiego. After the owners laid off most of its staff in June 2010, Stone took a job a month later as a local editor for Patch.com. In August 2013, he was laid off again, but his own website continues to thrive and gain followers.

Stone’s track career began in the fourth grade (1963-64) in a “race to the fence and back” at Centralia Elementary School in Anaheim, CA. His 2nd-place finish “lit a fuse that is still burning today.” His first formal competition took place a year later, on a Buena Park Boys Club team that bused to Arcadia High School (where the Arcadia Invitational now takes place). “Wearing clunky tennis shoes,” he says, “I took fourth in my first race – 75 yards on hard dirt. A few minutes later, I shed my shoes and took first in the 60-yard dash in socks. More success. A little taste demands more.”

A quick note: back in Stone’s day, all races were measured in yards in the United States. And hard dirt tracks, sometimes called cinder, are almost extinct. I would assume that most readers of this article have no recollection of them. The same can be said for the heavy metal hurdles with the wooden crossbars that he cleared when he first tried hurdling at Kraemer Intermediate School in 1967. Kraemer had a grass track, which is basically a mowed field with lines burned into it. Those are also obsolete.

There is no deep, meaningful story explaining why Stone first tried hurdling, but there is a funny one:

“Mainly I was a sprinter and high jumper. As a freshman [at Valencia High School in Placentia, CA], my coach, Robert ‘Mike’ Cummins, called track wannabes together and read off everyone’s name. They were to announce their event. My name, being near the end, meant that I could see where everyone else was entered. Too many sprinters, so I called out: ‘Hurdles!’”

Coach Cummins emphasized technical details and was way ahead of his time when it came to filming practice sessions. He would have Stone and the other hurdlers study their spike marks in the dirt in order to pinpoint ideal take-off and landing spots. One day, he rolled out “a huge audio-visual cart with a monitor and videotape recorder” so that the hurdlers could see their form and analyze their flaws.

Under Coach Cummins’ guidance, Stone thrived as a hurdler. His freshman and sophomore years he ran the 120-yard lows. The race consisted of five hurdles, 30 inches high, set 20 yards apart. Stone set a school record of 13.7 his sophomore year.

One of his craziest memories from his sophomore year is that of running the 4×120 shuttle low hurdles at a few invitational relay meets. Instead of the modern configuration in which four teams run at once, with one lane of hurdles facing one way and the hurdles the next lane over facing the other way, they ran in all eight lanes. “The first and third legs [ran] with the hurdles and the second and fourth legs [ran] against the hurdles. I was anchor every time, and Valencia won most races.”

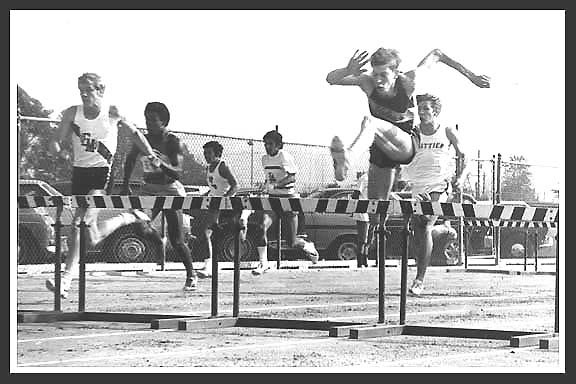

Stone (right) runs the shuttle hurdles with hurdles facing the wrong way (!).

Stone (right) runs the shuttle hurdles with hurdles facing the wrong way (!).

As a junior, Stone moved up to the 120-yard high hurdles (39 inches) and 180 lows. The 180 lows have since been replaced by the 300 intermediates. It consisted of eight 30-inch barriers spaced 20 yards apart. Stone ran the highs in 14.9 (all races were hand-timed back then) at the age of 16, the fastest time by a junior in Orange County in 1971. He was Orange League champion in both hurdle races that year, beating two senior teammates.

Between his junior and senior years, Stone’s family was forced to move from sunny California to cold, windy Nebraska so that his dad could keep his job. In Omaha, Stone attended Harry A. Burke Senior High. The transition was a difficult one, but he managed to continue his success on the track. At the Nebraska state meet, he ran 14.4 in the highs to finish fifth. He took fourth in the lows, with a season best of 19.9. He was the fastest hurdler in Omaha that year, but laments that he “would have run 14.1 or 14.2” had he been able to stay in California his senior year. He also points out that his 14.4 would’ve been fast enough to win states the previous and following years.

Still, the 120HH final from the state meet stands out as the most satisfying race of his high school career. “It was held at my own high school,” he recalls, “and my fan club (two girlfriends) were at the fence at the start, wishing me luck. I still vividly recall how I bumped arms with the kid in the next lane for several hurdles – we had different lead legs. And the race went by so fast I didn’t even have time to breathe! Then my coach in the stands rushed down to report that I had set a school record. Sweet.”

After graduating high school in 1972, Stone walked on to the Kansas University track team, although that had not been his original plan. He had been recruited by smaller programs like Chadron State College in Nebraska, University of Nebraska-Omaha and the University of Wyoming. But his heart was set on attending prestigious Ivy League institution Princeton University. That is, until he discovered that Ivy League schools didn’t give athletic scholarships.

He then wrote a letter to the coaches at Drake University in Des Moines, IA (where the Drake Relays are held every April), only to be told that they didn’t need any more hurdlers. He then wrote to University of Nebraska coach Frank Sevigne and arranged a meeting with him. “But when I showed up at the track office, I was told: ‘He is traveling with the football team.’ What? I had written ahead!”

Finally he began corresponding with an assistant at Kansas, inspired by the great reputation of its top-rated journalism school. Though Kansas didn’t offer any scholarship money, the opportunity to pursue a major in journalism there proved too enticing to pass up. So he walked on at Kansas, “having recruited myself.”

Stone’s track career at KU lasted two years, at a moderate level of success. He ran personal bests of 14.9 over the 42-inch high hurdles, and 56.1 (twice) over the 440-yard intermediates. With a best of 50.0 for the flat 440, he feels as if his long-hurdles PR should have been better.

As for collegiate hurdling ups and downs, Stone wryly remarks that his most memorable moment was also his most embarrassing. It came during an indoor dual meet at Nebraska in 1974. His dad, who had seen him run only once in high school, traveled from Omaha to Lincoln to watch him race. Stone describes the scene:

“In the 60-yard hurdles, I had a sensational start! Leading at the first hurdle! The second! Still ahead at the third! I leaned at the tape. My God! I had beaten teammates and national-classers Greg Vandaveer and Delario Robinson. Then I heard the crowd. Laughing. I didn’t hear the recall gun.”

His last collegiate race, in May of the same year, was similarly deflating. He had been told by his coach Thad Talley – the same Thad Talley who had coached Olympian Tom Hill to a 13.2 world record at Arkansas State in 1971 – that unless he did well in the KU-Kansas State dual meet in Lawrence, he would be cut from the team. “I got psyched, blasted out of the blocks, and reached the first hurdle first. But even with a 7-step approach, I crashed the first hurdle and was out of the race. KU career kaput.”

But while his career as a collegiate hurdler was coming to an end, his career as a journalist was beginning to blossom. He aced most of his classes, was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa honor society, served as associate sports editor of the University Daily Kansan (the campus newspaper), worked as the sports editor and then features editor of the Jayhawker yearbook, and also wrote for Kansas Alumni magazine.

Though Stone’s collegiate athletic career ended prematurely, his passion for track and field continued to grow. That initial thrill brought on by that fourth-grade race to the fence and back had set him on a lifelong path. Following his graduation from Kansas, he continued to pursue his mutual loves for writing and for competing. And he combined them by writing about track and field, covering many major meets over the years.

In his first job out of college, he worked as a sports editor and reporter for the Lamar Democrat, “a five-day-a-week afternoon paper in the county seat of Barton County, Missouri.” He made $120 a week. And covered a 0-9 high school football team. After seven months he returned home to California.

Stone’s big break came in March 1986, when he landed a job with the afternoon San Diego Tribune. He was hired after acing a tryout on the news copy desk. He was a news editor until 1999, when he moved to the sports copy desk. In 2003 he joined the Union-Tribune’s website.

Meanwhile, on the competing side of things, he continued to take part in the high jump until the age of 30, when he tore his ACL in his non-take-off leg after jumping 6 feet that year (1984). “I thought my track career was over,” he said. But 11 years later, at the age of 41, he tested his leg and discovered he could still jump. “So I did only the flop my first season back (1995) until the last meet of the season, the ocean-overlook Club West Masters Meet at Santa Barbara City College, when I ran 100 meters in 12.8 and was thrilled to survive the exertion.”

As is often the case with athletes who compete beyond their youth, Stone’s masters career has been riddled with injuries. He broke his ankle at the eighth hurdle at the 1998 USATF Masters Nationals in Orono, Maine. “The guy in the next lane hit his hurdle into my lane on the homestretch [of the 400m hurdles]. I landed awkwardly and my left ankle began to swell immediately. I watched the rest of the meet with my foot elevated and packed with ice.” Fortunately, he made a full recovery within a year.

In 2002, while running the 100-meter hurdles at the Santa Barbara meet, he couldn’t quite make his three steps. On the sixth or seventh hurdle, he landed with his center of mass behind his knee. He fell hard to the ground, breaking his wrist and tearing his left ACL. He had issues with knee instability until finally going under the knife for reconstructive surgery in 2007, which fixed the problem. He considers it “bulletproof healed.”

In 2013, he returned to the 400 hurdles, at the age of 59. His time of 1:32 may not have been up to his standards, but he was the oldest 400 hurdler in the nation last year. In June he turns 60, which means the event shortens to 300 meters in his age group, and height drops down to 30 inches. “Back to the lows!”

To enable his body to put up with the pounding, Stone takes a couple days off to heal after serious work. He rarely hurdles in practice anymore. On average he trains about two or three days a week. He plans to continue competing for as long as his body will allow him to. “I just ignore those who suggest I should quit hurdling,” he says. “My wife supports me, but some family members worry I’ll tear up my ACLs again.” To explain what keeps him going, Stone comments, “I’m a track guy. Can’t stay away. Defines who I am. Makes me feel superior to 99% of humanity.”

Stone clears a barrier in a 400 hurdle race. Not bad form for an old guy.

Stone clears a barrier in a 400 hurdle race. Not bad form for an old guy.

He adds that running at the masters level isn’t as intense as competing in high school and college, that it’s more about challenging himself than it is about finishing first. “When I surprise myself,” he says, “it’s a bonus. I also believe strongly that everyone should have a dangerous hobby. Masters track is that for me. Another big difference with high school and college is that I’m not told what to do. My ancient slogan: Why do they call us masters? Because we’re not slaves anymore!”

On the writing side, Stone started up the masters track website in February 1996. Why? “Mainly because I’m a glutton for attention and thought masters track deserved love too.” The site took off in 1999, when Dave Clingan combined his season listings with Stone’s “news nuggets and rants” and they registered the masterstrack.com domain name, an upgrade from its original position as an AOL page. In 2003, Stone started blogging on the site, and the site now has nearly “29,000 legit comments — not counting millions of blocked spam.” Thanks to Stone’s site, the phrase “masters track” has become common in mainstream media. Stone recalls that as early as the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, when the site was still an AOL page and only a few months old, a British gentleman struck up a conversation with him and said he had visited the site.

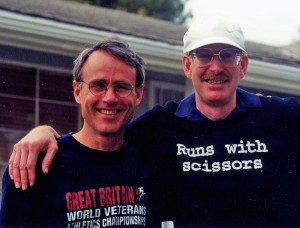

Stone (right) with masters middle-distance runner and website partner Dave Clingan.

Stone (right) with masters middle-distance runner and website partner Dave Clingan.

Over the years, Stone has covered many track & field events and has interviewed some pretty big names, including KU alums Wilt Chamberlain and legendary distance runner Jim Ryun. Chamberlain, known more as perhaps the greatest basketball player of all time, was a 7-foot high jumper in college. Stone interviewed Ryun “a half-dozen times, including covering his farewell to elite track at a KU press conference for Track & Field News. He interviewed four-time Olympic gold medal winning discus thrower Al Oerter for the July 1978 issue of T&FN, which may be the only interview ever conducted by that magazine by a non-staff writer: www.trackandfieldnews.com/archive/Interviews/Al%20Oerter.pdf.

An absolute track nut, Stone has taken part in the sport as an athlete, writer, and webmaster since the late 1960s. He saw most track and field sessions at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics and 1996 Atlanta Olympics. He also attended the 1988, 1992, 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012 U.S. Trials, twice as a blogger. He was the first person to live-blog the US Trials – in 2004 in Sacramento: http://web.archive.org/web/20080714110210/http://signsonsandiego.com/sports/olympics/weblog/. In 2008, his blog was the inaugural winner of TAFWA’s (Track and Field Writers Association) award for excellence in online journalism: http://tafwa.org/awards/adam-jacobs-memorial-award/.

For Stone, hurdling and writing are not separate ventures, but two distinctive aspects of the same venture — to challenge himself, to take chances without worrying about how he will look, or what people will think. “In college,” he reflects, “I was doing research at Watson Library and found a Life Magazine with the most amazing quote: ‘Hurdling is good training for a writer.’ Hurdling and writing both take discipline. But once you’ve mastered either, it’s a cinch. I never have writer’s block. I never worry about my form.”

When asked to explain why he loves hurdling so much despite his age and the injuries he has suffered, Stone replies by saying that “it’s a full-body sport that separates you from mere Muggles. I ran 180 lows in January 2014 for the first time in 41 years, and it was still a kick. Hurdling is in my DNA and to do it nearing 60 is a thrill. Fewer than 100 American men over 60 are listed as having run hurdles in 2013. Great to be in such select company. Old hurdlers rule!”

Stone encourages young hurdlers to learn how to alternate at an early age. It’s a skill that proves valuable in the intermediates. “And if you can keep your weight down, your courage up and your body fit, hurdling post-40 puts you in an elite class. After 50, you can look down from the clouds on all lower forms of athlete. Hurdling is the event of the gods. Everything else is for sissies.”

[/am4show]