Bent Leg vs. Straight Leg

Over the past two decades or so, there has been a lot of discussion about the benefits of the bent leg lead leg, as the straight leg lead leg had been the traditionally accepted style for many years. And though I’m a proponent of the bent leg lead, I also feel that the argument itself represents an oversimplification of what we actually want the lead leg to do. My thing is, it’s not about whether to have a bent lead leg or a straight leg, but about enabling the lead leg to cycle. Ultimately, the lead leg must straighten up at some point during hurdle clearance, so even a “bent” lead leg doesn’t stay bent.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

…Want to read the rest?

Subscribe Now!

[/am4show][am4guest]

…Want to read the rest?

Subscribe Now!

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

What is a straight leg lead? Basically, it is a lead leg that locks at the knee. In the photo below of Jason Richardson, you can see that his lead leg is straight as he is on top of the hurdle. This is what a “straight leg lead” looks like.

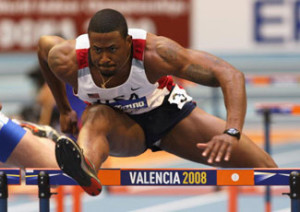

What is a bent leg lead? Basically, it is a lead leg that stays partially bent at the knee. In the photo below of David Oliver, you can see that his lead leg is still partially bent as he clears the hurdle. This is what a “bent leg lead” looks like.

Coaches and athletes who prefer the lead leg to snap down on the other side of the hurdle style want a straight lead leg. After the hamstring has passed the bar, the lead leg snaps down powerfully. The angle with this style are very rigid. The lead leg is parallel to the track while on top of the hurdle, then snaps down to perpendicular to the track upon landing.

To me, the term “bent leg lead” is misleading. A lead leg that remains bent throughout the entire hurdle clearance will cause the hurdler to buckle upon landing, as his hips will drop.

The term I like to use for the lead leg is a not straight nor bent, but a cycling lead leg. I like that term cycling because that’s what we want the legs to do with every stride, not just the stride over the hurdle. In a regular sprint stride – or, for hurdlers, in the strides between the hurdles – we want the legs to extend while the foot is on the way down, attacking the track. We don’t want the legs to extend horizontally. Obviously, that would be very difficult to do, first of all, and it would be very inefficient as well. So my thing is, over the hurdle, mimic the cycle motion, or continue the cycle motion, that you execute between the hurdles. Logically, it makes no sense to cycle for three strides then kick on the fourth stride.

To cycle the lead leg does require that the hips already be above the crossbar so that the hips can push forward without the need to elevate during take-off. For almost all female hurdlers, as well as for taller male hurdlers, the hips are already above the bar, so it makes sense to cycle the lead leg because that would be the most effortless (and therefore the most efficient) manner in which to attack the obstacle. For smaller hurdlers, there will need to be a vertical element with the back leg at take-off so that the hips don’t have to elevate.

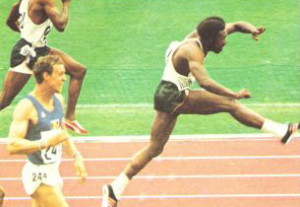

Another way of looking at this topic would be to identify which muscles are doing the most work. With the straight-leg lead, the hamstring is doing most of the work. The knee drive is relatively minimal, and the foot kicks out sooner, requiring the horizontal extension of the leg to cover the distance over the hurdle. That’s why a lot of hurdlers with straight-leg leads suffer from hamstring strains. The thrust of the kick also puts strain on the groin of the trail leg, which is why hurdlers with straight-leg leads also tend to have chronic groin issues on the trail leg side. The photo below of Rodney Milburn serves as a visual of what a straight leg lead looks like as it attacks the crossbar.

It’s also worth noting that straight leg leads do end up un-straightening (bending) the knee on the way down, before re-extending it just prior to touchdown, which, to me is an extra motion that wouldn’t be necessary if they’d wait to straighten the leg on the way down to begin with, as in a typical sprint stride. The photo below of Allen Johnson – who was a master of the bent leg lead, demonstrates that the leg does, in fact, extend during descent. Again, this mimics the typical sprint stride, which is what hurdlers want to do.

With bent-leg leads, or hurdlers who don’t extend horizontally, but on more of a downward angle, the hip flexor of the lead is doing the bulk if the work, not the hamstring. The hip flexor allows for an exaggerated knee lift, so that the knee is well above the bar, enabling for a downward angle as opposed to a horizontal angle. The hurdler is attacking the track, not just the hurdle, when extending the foreleg. Therefore, there is no need to snap down, as you are already descending.

A final, and very important point, would be that the straight-leg lead creates a pause in the action prior to snapdown. When the lead leg reaches full extension horizontally, there is a pause prior to the snapdown and the pull-through of the trail leg. This pause disrupts the rhythm, creates more work for the athlete, and therefore this style becomes difficult to sustain over the course of a flight of ten barriers.

[/am4show]