Front Side Mechanics for Hurdlers

If you ever listen to conversations between sprint coaches, you’ll often hear the phrase “front side mechanics” come up. Though it’s been around for decades, I didn’t first hear about it until November of 2004, when I attended a coaching clinic at the University of South Carolina headed by Coach Curtis Frye. One of the speakers at the clinic was biomechanist (and former 400m hurdler) Ralph Mann, who gave a detailed explanation of front side mechanics and its benefits. Ever since then, I’ve tried to employ the principles of front side mechanics when coaching my sprinters and hurdlers, and it has since become a foundational base for my teaching not only of sprinting mechanics, but also of hurdling technique.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

It could be argued (and I will, for the sake of argument) that all flaws in hurdling technique are rooted in flaws in sprint mechanics. Therefore, by eliminating flaws in sprint mechanics, the flaws in hurdling technique will either fix themselves or will be much easier to fix once directly addressed.

But more on that in a minute. First, let’s address the question, What is front side mechanics? It’s pretty complicated, but I’ll try to explain it in a way that is clear and direct. I would start with this simple explanation: instead of pointing your knees down and kicking back, you lift your knees up and drive forward. So, instead of having most of the stride take place behind you, it takes place in front of you. Hence the term, front side mechanics.

Here are some basic principles of front side mechanics:

1) The ankles must be dorsi-flexed, meaning the toes are pointing upward, throughout the entire sprinting stride. Many athletes run with their toes pointing down, which causes them to reach for the track with the foreleg. Others may run with their ankles dorsi-flexed when the foot comes off the ground, but then point the toe downward when cycling the foot back downward, which causes that same reaching action. This action is very inefficient because you always land with your hips behind your foot, causing you to prolong your ground-contact time. It also inhibits you from being able to attack the track with force.

2) The knee and heel rise upward together. The forward aspect of sprinting comes from the hips. You don’t want your knees or heels going forward; you want them going upward. When the knee is at full height, the heel should be under the hamstring, with the toe pulled upward, facing the front.

3) Once the knee is at full height, you want to attack the track with force, cycling the heel back under the hip.

4) Every step lands on the ball of the foot. I never tell my athletes to run on their toes. I tell them to run on the balls of their feet. If they’re running on their toes, their toes are pointing down, and their toes cannot support their weight. Running on the balls of the feet minimizes ground-contact time and serves to create the “bouncing” feeling that is so essential to efficient sprinting, which is a matter of covering maximal ground with minimal effort.

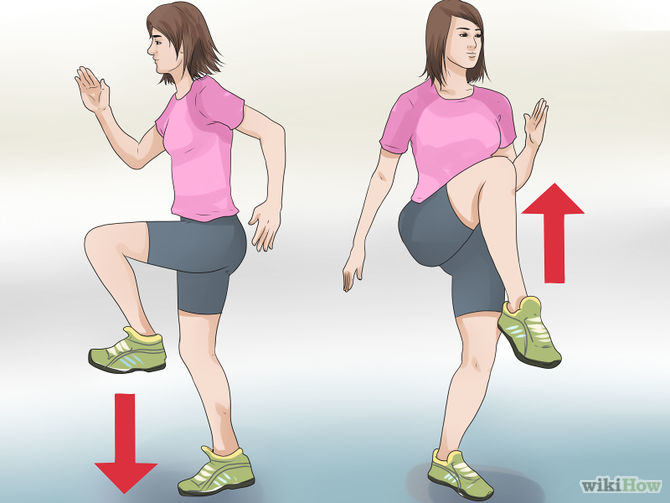

This image from the wiki.how page on sprinting faster shows the basic do’s and don’t’s of sprint mechanics. The girl on the left has the ankle dorsi-flexed, with the toe pointing up, the heel directly beneath the hamstring, thigh parallel to the track. The girl on the left has her ankle plantar-flexed, with the toe pointing down. Her knee is too high, and she’s rocking back on the heel of the foot on the ground.

These three big-time sprinters (Gatlin, Powell, and Carter) demonstrate the bouncing, floating sensation that occurs when sprinting is done properly.

Now let’s address the next question, which has to do with how front side mechanics applies to hurdling. One thing I tell beginning hurdlers is, if you know how to sprint properly, you already know how to hurdle properly, because hurdling is nothing but sprinting over hurdles. For girls, the amount of deviation from the sprint stride when going over the hurdle is minimal. Females can almost literally sprint over the hurdles. For males, a raising of the center of mass is usually required, as is an exaggeration of knee lift (lead leg) and an exaggeration of hip flexor rotation (trail leg). Sprinters and hurdlers who have a lot of back-kick in their stride often complain of sore hip flexors when they first learn to employ front side mechanics, and that’s because they’ve never really used their hip flexors before with their old way of sprinting.

Common flaws in hurdling technique that are a direct result of back-kick, and that can be corrected by learning front side mechanics, would be the following:

- The foreleg of the lead leg kicks upward and locks at the knee when attacking the hurdle.

- The lead leg swings from the hip, with no knee-first action at all, when attacking the hurdle.

- The last step prior to take-off is a stomp on the entire foot instead of a push on the ball of the foot.

- The trail leg knee points down and the heel kicks the butt after take-off into the hurdle.

- The hurdler is too erect throughout hurdle clearance.

- The lead arm crosses the body when the lead leg attacks the hurdle.

- The trail arm swings away from the body when the lead leg attacks the hurdle.

- Both arms swing away from the body (parachute arms) when the lead leg attacks the hurdle.

Let’s take a closer look at the above flaws. If the hurdler sprints between the hurdles with a lot of back-kick, then flaw #1 or flaw #2 will occur as a result. You can’t lead with the knee when your knee is pointing down.

If the hurdler is not on the balls of his feet in the strides between the hurdles, then flaw #3 will occur. He or she will not be able to take off on the ball of the foot if he or she has not been running on the balls of the feet when approaching the hurdle.

Back-kick means the heel of the back leg is facing the sky. From that position, flaw #4 will occur. The trail leg’s flight has to be wider because the knee of the trail leg is not coming upward, not facing the front. Hurdlers with back-kick in their sprint stride can never get the knee of the trail leg to face the front upon landing (they will always land off-balance).

An aspect of front side mechanics is that you have a natural forward tilt just by being on the balls of your feet. That tilt becomes a “lean” or “dip” when clearing the hurdle so that forward momentum can be maintained. Athletes who run with back-kick don’t have that natural forward tilt, so it’s very hard to lean while clearing the hurdle. Hence, flaw #5 is the issue.

When the lead leg kicks, when the trail leg swings widely, balance problems occur, and the arms try to compensate, leading to flaws #6-8. In some cases, the arm action during the strides between the hurdles is already more side-to-side instead of straight up and down, but that’s not directly a back-kick issue, although it often goes hand in hand with back-kick.

So if you take a careful consideration of the above paragraphs, you can see how it’s true that many hurdling flaws are rooted in sloppy sprint mechanics, and can be corrected by addressing the sprint flaws.

Which leads to the next question: how do you address the sprint flaws? How do you get a hurdler who sprints with back-kick to learn front side mechanics?

The answer is: slowly. Tediously. You’re talking about a major overhaul here, a major project. It’s paramount to learning how to walk all over again. Front side mechanics, when done properly, means you’re legs are cycling, not just stomping. Exercises to strengthen the hip flexors and hamstrings need to be incorporated so that the athlete can perform the actions properly without fatiguing too soon. Overall core strength (abdominals, lower back, groin, glutes) will need to be improved as well. You can’t run with front side mechanics if your body will not allow you to.

But in terms of learning the motions of front side mechanics, I would go in the following order:

- A-marches in place.

- A-marches ten meters.

- A-skips, 20 meters.

- Marching pop-overs over low hurdles.

- Quick-steps over low hurdles.

Coach should guide the athlete every step of the way, nit-picking at every mistake, stopping the athlete in mid-rep if necessary. Don’t move on to the next drill until the previous drill has been mastered. Both coach and athlete must be very patient. I’ve spent entire workouts teaching athletes A-marches and A-skips.

With the marching pop-overs, set up 4-10 hurdles at a height at least three inches lower than race height (I’ve used training hurdles and lowered them to 24 inches in some cases), and have the athlete A-march to the first hurdle and between the hurdles. Hurdles should be somewhere in the range of 10-15 feet apart for a three-step march rhythm in between. In this drill, the goal is for the hurdler to simply continue over the hurdle what he or she is already doing between the hurdles. If you see flaws in the approach to the first hurdle, or in between the hurdles, point them out and make the athlete start the rep over. As long as the coach is emphasizing that the in-between part has to be done right, the athlete will learn to focus on that aspect more, and will gradually come to understand the relationship between sprint mechanics and hurdle mechanics, and how the sprint mechanics sets up the hurdle mechanics.

With the quick-steps, the hurdles again should be at least three inches below race height, even lower if necessary. Again, 4-10 hurdles will do, with the hurdles anywhere from 18-24 feet apart. Here, the athlete takes a high-knee approach to the first hurdle, speeding up in the last two strides before the hurdle, then he or she continues with a three-step rhythm over the rest of the hurdles. Again, the key here is to do over the hurdles what you are already doing between the hurdles. Don’t add force, don’t add power, don’t grunt. Just continue to cycle, continue to run on the balls of the feet, continue to keep everything on the front side.

Over time, as the athlete adapts to this style of running that felt so “weird” at first, he or she can try sprinting faster, and incorporating higher hurdles spaced farther apart. But the coach must guide the progress and ensure that the athlete doesn’t try to skip steps on the way to mastery.

[/am4show]