Hamstring Strains: The Hurdler’s Curse

Of all the injuries that plague hurdlers, hamstring strains may be at the top of the list. If you’ve ever run the hurdles, you’ve probably experienced a time when you’ve felt a twinge on the underside of the thigh, or maybe a “funny” feeling, and you kept on going, thinking it wouldn’t amount to anything significant. But that funny feeling ended up leading to a strain or full-blown tear. If not treated properly, or if the return to action is too swift, a hamstring injury can destroy a season. In my years as a coach, I’ve noticed that while the hamstring strain isn’t the most common injury I’ve seen, it is the one that has been most damaging. This article will discuss causes of hamstring pulls, ways to prevent them, ways to treat them, and how to come back from them.

First, what is this thing we call a hamstring? According to Kelsey Armstrong, the podiatrist and track coach whom I consulted for last month’s article on shin splints, “There are three major muscles that make up the hamstring: bicep femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus (there is another muscles, adductor magnus, which some people consider a hamstring muscle, since it functions like them). Generally, they cause hip extension and flexion of the knee. The bicep femoris has additional functions of rotating the knee and hip laterally (outwards), which is important, because the biceps femoris is the muscle usually injured. The ‘semi’ muscles additionally cause rotation of the knee and hip medially (inwards). They are mainly postural muscles, which means they are reactive to changes in body position.”

Generally speaking, hamstring strains are caused either by fatigue in the hamstring muscles, or by a weakness in surrounding muscles. While there are many causes of hamstring strains that aren’t specific to hurdlers, I’ll start with one that is: poor hurdling technique. A lead leg that swings from the hip instead of leading with the knee puts a lot of tension on the hamstring. Similarly, a lead leg that kicks forcefully and locks at the knee also puts a lot of tension on the hamstring. In both cases, the tension in the muscle prevents a fluid motion. Over time – over a series of reps over a flight of hurdles – the hamstring will fatigue. Armstrong points out that a strain is often due to muscle fatigue. “In the case of hamstrings,” he says, “fatigue can be due to unfamiliar or highly stressful exercise.” So to reduce this stress, it’s important to develop a lead leg that leads with the knee and that stays slightly bent throughout the hurdling motion.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

Flaws in sprint mechanics can likewise put unnecessary strain on the hamstrings. Particularly, if you don’t keep your ankles dorsi-flexed so that your toes are pointing up, the hamstrings will suffer the consequences. Instead of landing on the balls of your feet, you will land on your toes, with your feet in front of your hips. This type of landing causes a breaking action that forces the hamstrings to work harder to keep you moving forward.

In regards to running posture, Dr. Armstrong suggests that instead of looking for imbalances in the hamstring muscles, it is more important for a coach to “look at how the athlete moves,” since weaknesses in other muscles put more pressure on the hamstrings.

“I first look at the ankle joint and its range of motion,” he said. “If it is restrictive, this can place increased load on the hamstring. Then, I look at the hip joint and its mobility throughout the running motion. If this appears tight, then this increases hamstring pressure. If both of these are present, it could lead to over-striding also, with the foot landing far ahead of the body.” For a hurdler who reaches with the foreleg in the strides between the hurdles in order to keep the 3-step rhythm going, this type of running can lead to hamstring strains, and can also lead to the type of hurdling technique (kicking, locking the knee) that leads to hamstring strains.

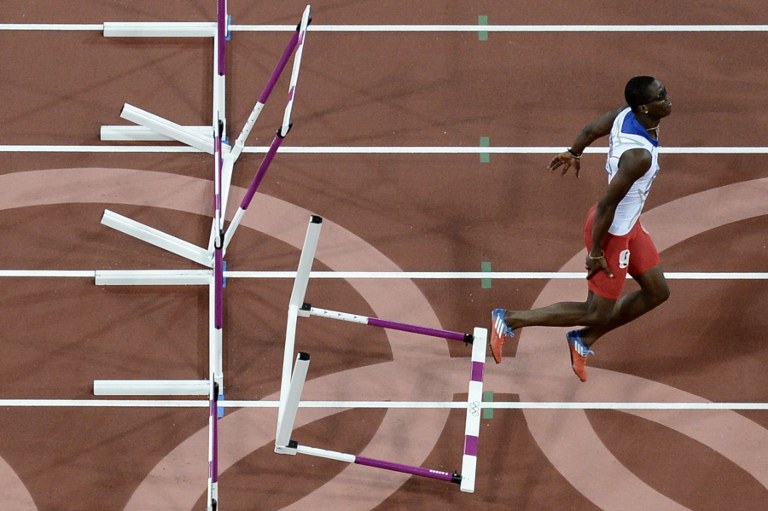

Cuban 110 hurdler Dayron Robles grabs his hamstring at the 2012 Olympic Games. (photo courtesy www.rappler.com).

Cuban 110 hurdler Dayron Robles grabs his hamstring at the 2012 Olympic Games. (photo courtesy www.rappler.com).

It’s important to note that proper technique is important not only when sprinting and/or hurdling, but also when lifting weights. Dr. Armstrong breaks it down:

“Improper technique could strain the hamstring, especially during Olympic lifts. For example, unstable stance/position during execution of the clean and jerk. Proper technique involves a full range of motion for back squats, dead-lifts, cleans, which allow the lower extremity muscle to function properly and build proper intramuscular coordination. The lifts I usually suggest for strengthening the hamstrings usually stress this coordination and utilize the hamstring’s function as a hip extender and knee flexor. These include Romanian Dead-lift (focus on hip extension), Single leg Romanian Dead-lift (great for postural control), and Glute Ham Raise (focus on knee flexion), either with a machine or without.”

From top to bottom, Romanian dead-lift, single-leg dead-lift, glute-ham raise.

From top to bottom, Romanian dead-lift, single-leg dead-lift, glute-ham raise.

(photos courtesy www.mensfitness.co.uk, www.womenshealthmag.com, and www.firstteamfitness.net, respectively)

However, strengthening the hamstrings in the weight room is not the only way to do so. Derek Hansen of www.runningmechanics.com, an expert on hamstring strains, published an article in September 2013 on hamstring strains among football players at training camps. Although the article focuses on football, much of what he says is applicable to track athletes, particularly sprinters and hurdlers. “A large proportion of strength coaches,” Hansen writes, “believe that weightlifting is the primary means of preparing athletes for [competition] and preventing injury…. I would argue that athletes must sprint several times per week in order to condition their hamstrings to resist injury…. The act of sprinting – accelerating and transitioning into upright running – places significant demands on the hamstring that are specific to sprinting. The combination of high forces and high velocities, combined with the coordination to switch-on and switch-off the muscles rapidly, can only be developed and optimized through regular sprint training sessions. Additionally, the sprint sessions must be organized with appropriate rest periods to ensure athletes are achieving high-speed efforts with good mechanics on every repetition.”

Hansen also points out that athletes must be in good physical condition, not just good sprint condition, because the same problem could still arise if the athlete jumps straight into sprinting without building an overall conditioning base. “I would argue,” Hansen writes, “that an athlete who is in good sprinting shape but in poor overall physical condition would still be in danger of muscle strain if [his or her] general fitness and recuperative abilities were poor.”

Another obvious cause of hamstring strains is a lack of flexibility. Arguably, hurdlers need to be the most flexible athletes on any track team, considering the positions in which they must put their body while moving at high rates of speed. To execute effective technique requires a certain amount of flexibility that allows for the necessary range of motion. If your hamstrings aren’t flexible enough to perform the motions, then chances are they will strain when trying to. Also, lack of flexibility in surrounding muscles, such as the glutes and calves and hip flexors, can force the hamstrings to work harder, thereby making you more susceptible to hamstring strains. For this reason, developing a static stretching routine after speed-based workouts is a good habit to get into. Static stretching after lower-body weight workouts is a good idea too, for the same reason. Lifting weights makes the muscles stronger, but it also makes them contract. To retain and increase elasticity, stretching after workouts is essential. Also, developing a yoga routine would be even better than regular static stretching, as yoga can not only increase flexibility, but can also improve posture and balance so that the muscles around the hamstring are more stable.

Any conditions in which you’re working out while your muscles are still cold increases the risk of a hamstring injury. Whether you’re sprinting/hurdling in cold weather, or without a full warm-up, or without sufficient warm-up clothes, cold muscles lack the elasticity necessary to function in the ways a hurdler needs them to. Too often I have seen athletes lazily perform their warm-up drills, or head out to the track in 50-degree weather wearing only a T-shirt and shorts, or try to go too fast (competing against their teammates) in weather that demands they slow down. In cold weather, the warm-up should be longer than usual, and some sprint drills should be doubled up. Also, the coach should adjust the target times for reps according to the weather. As for gear, athletes who compete in the sprints and hurdles should always wear tights while warming up, even in warm weather, just to ensure that the muscles do, in fact, warm up prior to the start of the workout.

As for training surfaces, Dr. Armstrong says that “softer surfaces are always better for injured athletes and newer athletes, as they allow the body to gradually get used to the stress of training, before the move to harder surfaces. The caveat is that you want the surface to have some ‘return,’ meaning your feet are able to bounce up after they hit the ground, as opposed to sinking into it. Too soft of a surface can lead to long foot contact, leading to prolonged hip extension and the possible hamstring strain.” So, while softer surfaces, such as a grass field or a bouncy track, are overall much more sprinter/hurdler friendly for training purposes than a harder surface, training regularly on these softer surfaces does put the hamstrings at risk.

US 400 hurdler Bershawn Jackson suffered a hamstring strain in the semi-final round of the 2013 World Championships. (photo courtesy of www.zimbio.com)

US 400 hurdler Bershawn Jackson suffered a hamstring strain in the semi-final round of the 2013 World Championships. (photo courtesy of www.zimbio.com)

Dr. Armstrong’s advice for preventing hamstring strains is pretty straightforward. First and foremost, train intelligently, and don’t over-train. If the workout says do ten reps and you’re feeling a twinge after the eighth one, stop at eight. Don’t try to push through those last two reps just to prove that you’re not a quitter. Listen to your body and do what it says. A good coach knows the difference between an athlete who is being smart and an athlete who is being lazy. Knowing that muscle fatigue is a leading cause of hamstring strains, trying to keep running through that initial twinge in order to complete a workout is more foolish than heroic. As Hansen warns, “As muscles fatigue and are placed under repetitive stresses at a high intensity, the risk of injury begins to skyrocket.”

Another preventative method is to emphasize the Mach A drills (A marches, A skips, A runs) in the warm-up, especially on speed days and hurdle days. These drills create a stretch that “causes tension to gradually decrease over time,” according to Dr. Armstrong. He also suggests “increasing the range of motion of the ankle joint complex by doing calf wall stretches, massaging the calf muscles, and doing other ankle joint mobilization exercises.” Finally, “increasing the mobility of the hip flexors will allow the gluteal muscles to work correctly and decrease the stress on the hamstring.” Mach A drills serve this purpose as well.

As for coming back from a hamstring injury, it’s a little trickier than you might think. While you don’t want to rush back too soon, sitting around doing nothing for two weeks isn’t a good idea either. “A strain,” Dr. Armstrong says, “results in scar tissue formation by at least seven days after the injury. The goal is to manage the first few days of inflammation with rest, but start some movement before the scar tissue sets in. Scar tissue increases the tension in the muscle due to causing contraction.” To prevent the scar tissue from setting in, basic drills are again the way to go. The Mach A drills in particular.

Beyond the drills, sprinting must gradually be incorporated back into the training regimen. As Hansen writes, “Given that the best means to prepare a hamstring for the rigors of sprinting is actual sprinting, it follows that an optimal hamstring rehabilitation program must include a progression of sprinting.”

This doesn’t mean go out and sprint full-blast or engage in a full-blown hurdle workout as soon as the hamstring feels better. A lot of times, the hamstring can fake you out into thinking it’s fully healed. You feel fine walking around on it, you feel fine doing your drills, so you think you’re ready to go. A lot of times it even feels fine when sprinting, but when you try to go over a hurdle, ahhh, there’s that twinge again.

To quote Hansen again: “Until physical therapists incorporate a systematic approach of progressively faster and long sprint intervals – with an emphasis on proper running mechanics – into their rehabilitation routine, athletes will have inconsistent and incomplete rehabilitation experiences when it comes to hamstring injuries.”

So for a hurdler, hurdling should be the last step in rehabbing a hamstring strain. After the sprint drills, then lighter sprints, then faster sprints – all pain-free – only then should hurdle drills be incorporated, and even then at lower heights and closer spacings. The last thing you want is a setback. And you have to understand, once you’ve injured your hamstring once, you are susceptible to a setback. As Hansen says, “the most significant predictor of hamstring injury is previous hamstring injury.” So when it comes to recovery, slow and steady is the way to go.

Work Cited

Hansen, Derek. “Hamstring Strains and Training Camp: What’s the Connection?” Running Mechanics: Optimal Movement for Peak Performance. WordPress, 13 September 2013. Web. 08 October 2013. <http://www.runningmechanics.com/hamstring-strains-and- training-camp-whats-the-connection/>.

[/am4show]