Trail Leg to the Front

by Steve McGill

One of the key aspects of the style of hurdling that I teach – a style that I refer to as “cycling,” similar to the style that Coach Curtis Frye of the University of South Carolina refers to as “rotary hurdling” – is that the leg commonly referred to as the “trail leg” never stops moving. It doesn’t pause after it pushes off. Also, the angle at which it drives to the front is intended to be as high and tight as possible, minimizing the flattening out of the leg and the opening up of the groin. I tell my hurdlers that we want our trail leg to almost match the action of the lead leg, allowing for as much opening of the groin as needed to avoid contact with the crossbar.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

The Allen Johnson Effect

Back in the day, when 1996 Olympic 110 hurdle champion (and current hurdles coach at North Carolina State University) Allen Johnson was training for the ’96 Olympics, a documentary came out on the Discovery Channel showing his training methods in preparation for the Games. (I can’t find footage of that documentary anywhere now, by the way). But anyway, Coach Frye was coaching Johnson at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill at the time, and in one part of the video he was explaining the rotary style that he was teaching Johnson. It was a style that featured a bent lead leg instead of a straight leg, and it also featured a trail leg that was high and tight.

Back then, almost all hurdlers straightened out their lead leg and then snapped it down with force. The trail leg just kind of did whatever. The emphasis was always on the snapdown of the lead leg as the primary way to generate speed off the hurdle. But what Frye had Johnson doing was very different. And, in my eyes, it was much more efficient and much more fluid.

The Liu Xiang Effect

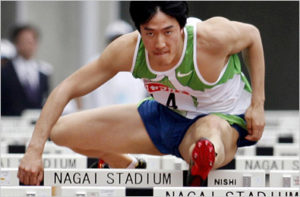

Fast forward to the Liu Xiang era, especially the 2004-2006 years. When he won the Olympic 110h final in 2004 in a dominant performance, my first reaction was, Who is this dude? He wasn’t nearly as muscular in the upper body than the other hurdlers, yet he had laid them to waste. What was he doing that they weren’t doing? I couldn’t figure it out. By the time he broke the world record in 2006, I was determined to figure it out.

Then it just so happened that a poster of Liu was included in an issue of Track & Field News, and in that photo he was clearing a hurdle, with the foot of his lead leg just about to reach the crossbar. What struck me as odd was his trail leg. It was so high. His knee was very high above the crossbar, whereas the trail leg knee of most hurdlers would be either even with the bar or below the bar at that point in hurdle clearance. How was he getting his trail leg knee that high that fast?

I went back and looked at video of his world record race, and one of the slo-mo angles revealed to me Liu’s secret sauce: his trail leg didn’t pause. Looking at other hurdlers, their trail leg paused after it pushed off the ground. Then, after that slight pause, the leg would “whip” to the front. But with Liu, there was no pause, and there was no whip. There was one continuous motion. What Liu was doing went against conventional wisdom. It boggled the mind. But the fluidity of it captured the imagination.

Though Liu’s style went against conventional wisdom, something about it resonated with me, and actually validated something I’d been thinking for quite a while: there’s no such thing as a lead leg that is too fast, that comes to the front too soon. If the lead leg stays slightly bent and doesn’t lock at the knee, the trail leg can follow right behind it.

Push Forward

Besides “cycling,” another name I give to the style of hurdling I teach is “downhill hurdling.” The idea behind it is to push off the back leg with force while driving the knee of the lead leg up so that it is higher than the crossbar, all while pushing the hips forward. The push off the back leg raises the hips, while the upward drive of the knee upward makes the hurdle small, and pushing the hips forward prevents any issues with floating.

So, what ends up happening is, you’re able to attack the hurdle at a downhill angle. For females over 33” hurdles, the downhill angle can be quite extreme. But even for males going over 39’s or 42’s, there can still be a slight downhill angle, but just not as steep. The key is to create the feeling that you’re just stepping over the hurdle.

The forceful push off the back leg is a momentum creator, a speed creator. And because the lead leg stays bent, the trail leg doesn’t need to pause. As the lead leg cycles back to the track, the trail leg can cycle right behind it, high and tight. The downhill angle coming off the hurdle puts the body in a position where it can’t help but speed up upon landing, just like you can’t help but speed up when you’re running down a hill.

I recently started working with a post-collegiate hurdler who is making a comeback after taking some time off. In evaluating his technique in our first session, it became evident to me that he was locking his lead leg knee, causing his trail leg to flatten out, causing his hips to twist, causing him to land off-balance. In discussing our plans to get him right, we agreed to tear down everything he was doing and rebuild his technique from the ground up.

So we went to a couple of my go-to drills – marching popovers and the cycle drill, with the intent of learning how to push off the back leg with force and to drive it instantly to the front without any pause. At first it was very difficult for him, even with the hurdles at 33 inches, because his lead leg had grown so accustomed to being the power leg, to kicking out. But once he started to grasp the concepts, he got the hang of it pretty quickly. When I asked him after one particularly good rep what cue he was telling himself, he responded, “Push forward.” Though I hadn’t used that exact phrasing with him myself, it exactly described what I wanted him to do. Push forward off that back leg, and drive it to the front. The video below is from our first session together, three weeks ago. The photos below the video are a sequence of screenshots I took of him clearing a 39-inch hurdle in the cycle drill.

[/am4show]