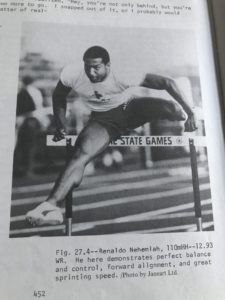

Is Renaldo Nehemiah the Greatest 110 Hurdler Ever?

by Steve McGill

As of this writing, I have written three chapters of the first draft of the biography I am writing on Renaldo Nehemiah. The first chapter focuses on his childhood years, with the emphasis on the death of his mother due to lung and breast cancer when she was only 37 and Renaldo was only 14. The second chapter focuses on his high school years, which is when he became the first prep hurdler to run under 13.0, as he ran a hand-timed 12.9 at a post-season meet featuring some of the best high school athletes on the East Coast. The third chapter, which I just finished a couple days ago, focuses on his first year of college (1978) at the University of Maryland. As I mentioned in last month’s issue, I’m becoming increasingly convinced that Nehemiah is the greatest 110m hurdler ever, as evidenced by race footage I’ve gained access to, and even more so as I continue to write the book and am coming to fully grasp the enormity of his accomplishments at a very young age.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

As a high school freshman at Scotch Plains-Fanwood High School in New Jersey, Nehemiah began his journey as a hurdler after focusing on football and basketball athletically for most of his life. In his first year of hurdling, he ran 15.3. He missed all of his sophomore year and part of the off-season of his junior year due to a major hamstring injury that ripped muscle from the bone. Once healthy, he followed the program of coach Jean Poquette, and his athletic skills flourished in a way that was stunning. His personal best dropped all the way down to 13.6, and he remained a star quarterback on the football team. Then, senior year, he dropped from 13.6 to 12.9 while also setting a state record in the long jump of 24’11 ½” — a record that would be broken by Carl Lewis two years later.

In his first year at UMD, he tied the indoor world record of 7.13 in the 60-yard hurdles in his fourth meet. In the fifth meet, the Millrose Games at Madison Square Garden, he broke the world record with a 7.07. He would later go on to win the 60-yard hurdles at NCAA Nationals. So, before his 19th birthday on March 24, 1978, Nehemiah was a world record holder and NCAA champion. Outdoors, he lost twice to UCLA’s Greg Foster. And if you’re familiar with that era, you know that the Nehemiah vs. Foster rivalry was at the center of the sport from 1978-1981. The second loss was at NCAA Outdoor Nationals, where Nehemiah ran 13.27 to Foster’s 13.22. Foster broke the American record previously held by Rodney Milburn, who ran 13.24 in the 1972 Olympic final. Nehemiah’s time set a new World Junior record. But he didn’t care about that because he hated losing. The final came right after the 4x100m relay, in which Nehemiah had run the anchor leg for UMD. He felt adamantly that if he had run that race on fresh legs, he would’ve beaten Foster. The next weekend, at the AAU National Championships on Foster’s home track at UCLA, Nehemiah got his revenge, running 13.27 to Foster’s 13.43. That summer, Nehemiah only lost once more — to a Russian hurdler at a meet in Eastern Europe. He beat Foster four more times, and finished the year ranked by Track & Field News as the number one ranked high hurdler in the world.

Let that sink in for a second. As a freshman, who didn’t turn 19 until late-March of that year, Nehemiah was already the number one ranked hurdler in the entire world. Not just in the ACC, or even the nation. He was the best hurdler in the world. His time of 13.23 at the Weltklasse meet in Europe was the second-fastest time in the world that year, second only to Foster’s 13.22 at NCAAs. As a 19-year-old freshman, he was only .02 off the world record of 13.21, run by Cuba’s Alejandro Casanas in 1977.

We all know how difficult it is for freshman males to adjust to college hurdling. The extra three inches changes a lot of things. In some cases, it requires totally tearing down and rebuilding one’s technique. Most hurdlers will see a significant drop in their personal best that first year, and it might take two or three years before they’re running as fast as they were in high school. Nehemiah was threatening the world record in year one over the 42’s. That’s a young man who was gifted.

One advantage Nehemiah had, however (which I talk about in the book), is that he began running over 42’s as a senior in high school. After he ran a prep record 6.9 in the 60-yard hurdles four times in the beginning of the indoor season that year, Coach Poquette threw him in the Millrose Games, where he ran against grown men like Larry Shipp and Charles Foster. Nehemiah finished fourth, but still, that was against grown men over 42’s. Later that year, Poquette would have Nehemiah run over 42’s in dual meets while the other hurdlers ran over 39’s. It was a way of keeping him from getting bored against weaker competition. Another of Poquette’s innovations was to have Nehemiah practice over 45-inch hurdles by adding extra padding on top of the crossbars. Nehemiah was only 6-feet tall practicing over 45’s. Those workouts weren’t done at full speed, but still, it served its purpose: it made the 42’s feel not so high. All the work over 45’s, as well as the races over 42’s, made the transition from high school to college much easier than it would be for most hurdlers.

I’m an advocate of having advanced high school hurdlers practice over 42’s the senior year of high school, and to race over 42’s if at all possible. I had an athlete several years ago, Booker Nunley, who was ruled ineligible to compete in high school meets his senior year because he didn’t take enough credits his first semester. The reason he didn’t take enough credits was because he didn’t need to take more than one or two classes to graduate. But he didn’t realize that not taking a certain amount of credits would affect his athletic eligibility. By the time he found out, it was too late. As a result, we had no choice but to train over 42’s and enter him as an open athlete in college meets. He ended up running 13.91 over 42’s that year and was running in the 13.5-13.4 range his first year of college before his career was derailed by a back injury.

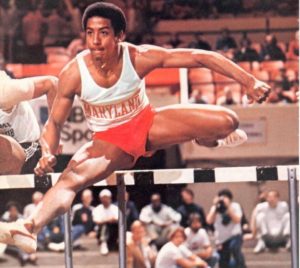

But getting back to Nehemiah, whether or not he is the greatest ever is arguable (and I’ll continue the discussion in future issues as I continue working on the book), but there’s no doubt that no one has arrived on the scene more emphatically than he did. Times he was running as a 19-year-old freshman over wooden hurdles on tartan tracks would still put him among the best in the world today. The most distinctive features of his technique was an upright running style, and super-quick lead leg, and a trail leg that rose very high as it drove to the front. I feel that the high trail leg was a key element in creating speed, as it was also a very distinctive feature of Liu Xiang’s style that I admired. Let me close this article with a couple photos of Nehemiah that show his high and tight trail leg. The first photo appears in the Track & Field Omnibook by Ken Doherty, and the second one was sent to me by Nehemiah’s teammate at UMD, Andre Lancaster.

[/am4show]