Renaldo Nehemiah and the 1980 Olympic Boycott

by Steve McGill

Those of you who have been subscribing regularly over the last several months are aware that I’m writing a biography on Renaldo Nehemiah, also known as “Skeets,” who set the 110 meter hurdle world record three times between 1979 and 1981. I recently completed the chapter that covers 1980 and the Olympic boycott that deprived him of the chance to earn what almost certainly would have been a gold medal. With the possible exception of Edwin Moses in the 400 hurdles, there was no athlete who was more of a sure bet to bring home the gold than Nehemiah. In this article, I will discuss the boycott and what led to it, some other things you might not know, as well as the boycott’s effects on the career of Nehemiah and other would-be Olympians.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

Heading into the indoor season of 1980, Renaldo was coming off a 1979 in which he broke the world record twice. First he broke Cuban Alejandro Casanas’ record of 13.21 with a 13.16, and then breaking his own world record with a 13.00 two weeks later. The only threat to his supremacy was arch rival Greg Foster, but Foster didn’t run at the 1980 USA Olympic Trials due to a bout with tonsillitis. But by then, President Jimmy Carter had already informed the athletes that the boycott was final. Otherwise, Foster probably would’ve given it a go.

Anyway, the boycott was rooted in the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan on Christmas day in December of 1979. The invasion didn’t seem like that big of a deal, or even very unpredictable, but the location of the Soviet troops seemed to be very strategic, as it was in the path of oil sources that the Western world relied upon. Also, with the history of the Cold War and the nuclear arms race, the bad blood between the USSR and the USA was always simmering beneath the surface whenever there wasn’t outright hostility. So, in addition to embargos, Carter and key members of his administration felt that a boycott of the Olympics would further hurt the economy of the Soviet Union, and that it would send a message that their bullying tactics would not go unpenalized. With Afghanistan being a Muslim country, Carter framed the invasion as a superpower taking advantage of a weaker country and intruding upon their religious freedoms.

One of the main arguments the potential boycott inspired, before it became official, was the degree to which sports and politics should mix. The Olympics, to many, was considered hallowed ground. The whole point of the Olympic movement was to bring together people of all races, all religions, all nations in the spirit of competition. But as I found out while doing my research, there never was a time when politics did not play a role in the Olympics. A few prime examples would be the Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler using the 1936 Olympics in Berlin as a showcase for Nazism. Hitler wanted to use the Olympics as a way to show the superiority of the Aryan race. He and his lieutenants wined and dined world leaders from other countries, who were very impressed with the Opening Ceremonies and with the displays of national pride throughout the city. He made it a point to shake hands with German gold medalists. When Jesse Owens of the USA won four gold medals in the 100 meter dash, 200 meter dash, long jump, and 4×100 meter relay, Hitler was nowhere to be found. Other examples of politics in the Olympic Games include the 1968 Olympics. Just a month prior to the Games, a group of student protesters was attacked and many were murdered by the Mexican government, who didn’t want the protesters ruining the picture of a country that was ready to host the most important international sporting event in the world. Then, in the Games themselves, there was the black-fist protest of Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the medal stand for the playing of the national anthem after the 200 meter dash. In 1972, there was the “Munich Massacre,” in which 13 Israeli athletes and coaches were murdered by Palestinian terrorists. In 1976, the Games were boycotted by many African countries in protest of apartheid in South Africa. In short, one would be hard-pressed to find an Olympic Games in which politics did not play a role. Even the very act of choosing a host country, by the International Olympic Committee, is typically a process laden with political implications. So, in that context, Carter’s choice to boycott the Olympics didn’t come out of a vacuum; it was consistent with history.

The reason that the 1980 boycott was so controversial was that many Americans worried that it wouldn’t be effective. Ultimately, they were right. The USSR didn’t leave Afghanistan for another nine years, and there was no evidence that even one Afghanistan life was saved by the actions of the USA and the other countries that joined the boycott. Ultimately, the only people who were hurt by the boycott were the athletes themselves. For Renaldo, it meant that despite his dominance in the high hurdles and his status as the best in the world and the best ever, he did not have a gold medal to add to his resume. In amateur sports, an Olympic gold medal was, and still is, considered the ultimate achievement. And even though there are no guarantees that Olympic gold will translate into more money in the bank, in Renaldo’s case, it probably would have. He already had the other intangibles–he was good-looking, well-spoken, at ease in front of a camera. Of course, any money earned back then would have had to go into a trust fund in order for him to retain his amateur status, but still, the amount of money the boycott cost him in potential endorsements was easily in the six-figure range, and that’s a conservative estimate. Ultimately, the boycott was the biggest reason he ended up leaving amateur track for the NFL two years later (which I discuss two chapters later). He had become completely disenchanted and disillusioned with amateurism as it existed at the time, and didn’t want to risk another four years of training if something similar were to happen. Indeed, the Soviets boycotted the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, although that didn’t affect the hurdling events very much at all.

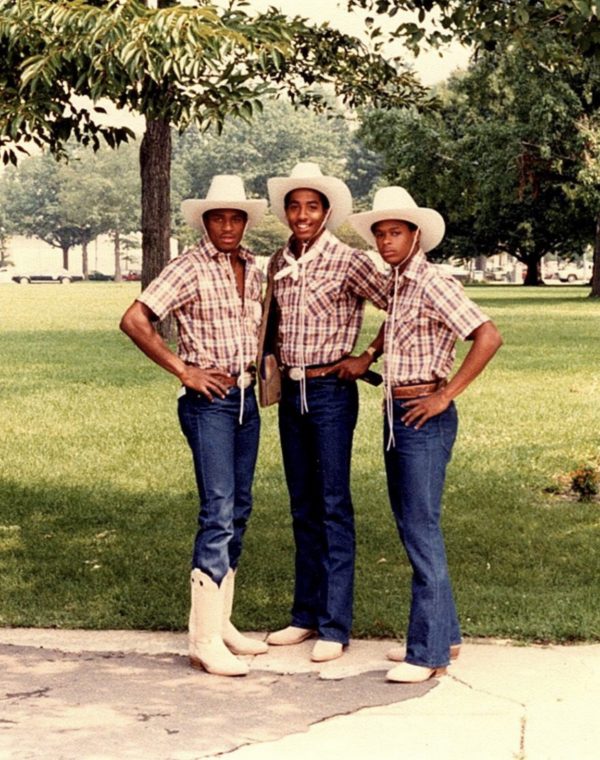

Nehemiah (center) and two other athletes in the cowboy outfits the Olympians would’ve worn at the opening ceremonies of the Moscow Games. Here, the outfits were worn during a picnic on the White House lawn held in honor of the Olympic athletes.

One of the people I interviewed for the book was Tonie Campbell, who finished third in the 110 hurdles at the Olympic Trials that year. Before the Trials, Campbell was considered to have only an outside shot of making the top three. But with his rapid improvement, coupled with Foster’s scratch, Campbell ended up making the team. His attitude toward the boycott shifted drastically after the race. Before, he was of the mindset that the boycott was justified if it were to save just one life. After the race, he realized that his dreams were being compromised by his government, and that was his moment of great awakening. Athletes like Campbell, Moses, and sprint/long jump sensation Carl Lewis were able to continue their careers and make subsequent Olympic teams and earn Olympic medals. For many older athletes, however, 1980 represented their only chance. For Renaldo, his four years playing professional football would have been his prime years as a hurdler. By the time he returned to the sport in 1986, the damage that football had done to his body meant that he would never be able to return to his past glory.

Nehemiah remained bitter about the boycott for a long time. It took him over twenty years to get the point where he was okay to even talk about it. Now, he says that no one race defines an athlete’s career. Despite not being a star with the 49ers, he did win a Super Bowl with them. He remains the only athlete to ever own a world record and a Super Bowl ring. When you get to know Renaldo, you come to understand that he is not the type of person, at all, to look back with regrets and to second-guess his decisions.

In next month’s issue, I’ll talk about Renaldo’s glorious 1981 season, in which he became the first hurdler to run under 13.00.

[/am4show]