Hurdlers I use as Models, and Why

by Steve McGill

It’s natural and common for hurdlers who are eager to improve to scour the internet for videos of professional and collegiate hurdlers, past and present, so that they can incorporate something they learn into their own style. While this practice is commendable, because it shows an unwillingness to settle for mediocrity, it can also be dangerous, because most the hurdlers who are running world class times are talented enough to do things that the pretty good high school hurdler cannot do. Or they may be doing things that are difficult to execute, so simply watching it and trying to mimic it probably won’t work.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

I have a very specific style of hurdling that I teach, so I’m very particular about guiding my hurdlers to specific professional hurdlers to serve as models of what I’m trying to get them to do. I’m not necessarily always looking at the hurdlers who are coming in first place. Plenty of hurdlers who never make it to the medal stand at a major championship are doing a lot of things right that are worth studying. In this article, I will discuss who my go-to hurdlers are to use as models when I’m coaching my athletes.

For my male hurdlers, my go-to athlete to study and analyze is (and probably always will be) Allen Johnson, who won gold at the 1995 World Championships, the 1996 Olympics, and the 1997 World Championships, and continued to have an outstanding career that spanned about 15 years. Watching Allen during his career, and picking the brain of his coach Curtis Frye, helped me to form my philosophy and approach to coaching the hurdles. In the run-up to the 1996 Olympics, a documentary appeared on the Discovery Channel detailing Johnson’s training in preparation for the Games. In this 30-minute documentary (which I can absolutely not find anywhere on the internet), Frye discusses what he referred to as the “rotary style” of hurdling that he was implementing with Johnson. The style emphasized a bent lead leg (which was a borderline revolutionary concept at the time), and a trail leg that followed right behind the lead leg with no pause or lag (which was also revolutionary at the time). Even though Johnson arguably had more success early in his career, it wasn’t until later in his career that he really mastered this rotary style to the point where he was running clean races while still retaining the power and aggression that defined his early-career victories. Prior to Johnson, almost all hurdlers placed a heavy emphasis on the lead leg — kicking it out and snapping it down. With Johnson’s emphasis on the trail leg, he brought in a more balanced, rhythmic hurdling style in which both legs functioned together as a unit.

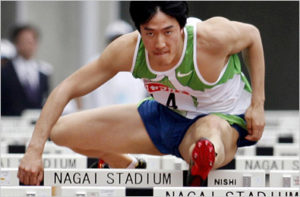

The other male hurdler that I point to as a technical master is 2004 Olympic champion Liu Xiang. My favorite feature of Xiang’s was his lead arm. I’ve seen a lot of funky lead arms over the years, especially from male hurdlers, but Xiang’s has always appealed to me the most. Xiang’s lead arm moved in a quick, precise up-down motion, with the elbow staying low and the hand never crossing the plane of the center of the face. The thumb stayed pointing up and never rose any higher than the forehead. Like Johnson, Liu’s lead leg stayed slightly bent at the knee, and he was really good at exploding off the ground into hurdling position, and then pushing back down to the ground on the other side of the hurdle. Xiang was a master of creating space by being super-efficient with his movements.

When it comes to female hurdlers, I put Sally Pearson on the same level that I put Allen Johnson on the men’s side. She has an excellent lead leg; she drives her knee forcefully at each hurdle, maintains a fluid cycling action with both legs, and also maintains a cycling action with her lead arm. I actually like her lead arm even more than Liu’s, even though Sally’s tends to cross her body a little bit. But the cycling action of her lead arm is what enables the natural cycling action of her lead leg. Of all hurdlers I’ve ever watched, I’d put Sally at the top when it comes to how her efficient technique, masterful sprint mechanics, and impeccable body positioning always puts her in position to win races. Many female hurdlers over the years have run very well despite glaring flaws simply because the hurdles are so low that the race is much more of a sprint race than the men’s. But Sally is as close to flawless as you can get, so she serves as evidence that even in the women’s race, technical precision does matter and is worth investing time in.

Another go-to female hurdler of mine is Dawn Harper-Nelson, pretty much for all the same reasons that I discussed above in regard to Sally. If you watch the 2012 Olympic final, you’ll see that Sally’s and Dawn’s hurdling styles almost mirror each other, as Dawn too drives very forcefully with her lead leg, cycles the lead arm, and brings the trail leg right behind the lead leg without any delay.

A third female would be Keni Harrison, whom I coached in her last two years of high school. So, I know that Keni was taught how to hurdle efficiently, and it is obvious that she continued to build upon the things I taught her after she moved on to college and then to the professional ranks.

Jasmine Camacho-Quinn serves as a great example for how short, quick, precise arm action can help taller hurdlers to negotiate the space between the hurdles without having to sacrifice speed. With the women’s hurdles being so low, height is often a disadvantage, but Camacho-Quinn has made it into an advantage. For hurdlers who are 5-7 or taller, Camacho-Quinn is the one they should be watching.

Going back to the men’s side, Jack Pierce from the 1990’s is another I like a lot and teach a lot, as he was ahead of his time when it came to smoothness and fluidity.

All of the hurdlers I’ve mentioned in this article are hurdlers whose hurdling methods fit the “downhill” style of hurdling that I teach, which emphasizes a big push off the back leg, a cycling of both legs (no kicking, no snapping), a deep forward lean from the waist, and a fluidity of motion that causes speed to happen without the athlete actually making an effort to increase speed.

Coaches with different hurdling philosophies might point to other hurdlers as their ideal models, and I’m perfectly fine with that. For me, fluidity = speed; fluidity doesn’t just make for aesthetically pleasing hurdling, but it makes for fast hurdling, and, more often than not, mistake-free, contact-free hurdling.

[/am4show]