You Will be Missed, Greg Foster

by Steve McGill

In November of 1983, two months after my seventeenth birthday, I was lying in a hospital bed, diagnosed with a rare, potentially fatal blood disease called aplastic anemia, characterized by bone marrow failure. The symptoms — extreme fatigue, unexplained bruises appearing on different parts of the body, a feeling of constant pressure on my ears, gums bleeding while brushing my teeth — had begun in the spring of my junior year. But it wasn’t until late-October of my senior year that I had a blood test done and received a diagnosis. Long story short, I spent three weeks in the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where I received treatment and then went on to make a full recovery.

I had gotten into hurdling relatively late in life. I grew up playing basketball and didn’t take up the hurdles until my sophomore year of high school. I fell in love instantly, and was the second best hurdler on our team after struggling as a flat sprinter. My junior year, despite my as-of-yet-undiagnosed illness, I finished fourth in my conference, and all the hurdlers ahead of me were graduating. So I entered my senior year with hopes of being conference champion. My diagnosis seemed to derail those plans. I didn’t know if I’d ever run the hurdles again at all, much less compete for a conference championship.

During my entire hospital stay — through all the emotional lows while dealing with the various side effects of the treatment and facing the very real possibility that I might not survive this illness — the desire to hurdle again gave me hope amidst my despair. It gave me a reason to want to live. The greatest hurdler in the world at that time was American Greg Foster, who had taken over the mantle a couple years earlier when, in 1981, his rival and world record holder Renaldo Nehemiah left the sport to play professional football for the San Francisco 49ers. It was Nehemiah’s world record race, which I saw on video two years after it happened, that inspired me to pursue hurdling as a passion. But by the time I had made that decision, Nehemiah was no longer in the sport, and now Foster was the man.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

I can remember, during my hospital stay, sitting in the play room and reading the edition of Sports Illustrated that featured a story on the first ever Track & Field World Championships, which had taken place earlier that summer in Helsinki, Finland. Part of the article focused on the men’s high hurdles, which Foster had won in a time of 13.42. A very slow time for him, but he had smacked a hurdle and almost fell, but managed to keep his balance and still win the race. In those dark and lonely days in the hospital, I must’ve read that article about fifty times. In my bed at night, feeling helpless in a body that was falling apart, I envisioned myself doing what Foster had done.

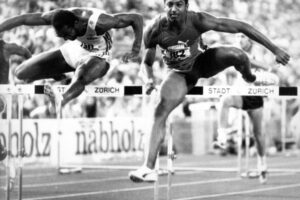

These are the memories that flooded into my mind when I heard that Greg Foster had passed away at the age of 64. On February 19, 2023, Foster passed away due to amyloidosis. Foster had been battling the illness for quite some time. He was diagnosed in 2016, underwent chemotherapy, and had a heart transplant in 2020. Though I didn’t know Foster personally and never had the chance to meet him, I consider him to be one of the key people in shaping my identity during my adolescent years and early adult years, as his reign at or near the top of the high hurdling world spanned a good 14 years — from 1977 to 1991. And as I said above, when I embarked upon my hurdling journey, he was the best in the world, the standard that all hurdlers strove to meet.

When looking at the arc of Foster’s career, there is no doubt that he is one of the greatest hurdlers who ever lived, and that he belongs on anyone’s top ten list in the 110’s. Ironically, his personal best came in a second-place finish, when he ran 13.03 in Nehemiah’s 12.93 race — the first race ever officially under 13.00. Foster’s technique back then wasn’t nearly as good as it would come to be as he continued to progress. Back then, there was nothing about his technique that my older coach self would like. His lead leg locked at the knee (which was very common among hurdlers of that era), his head ducked down, his trail arm swung out wide, and the hurdling action as a whole took up too much space. That’s why he was so prone to hitting hurdles and falling. Back then, we all thought it was because he was too tall and so strong. But now it’s clear that his technique was the issue.

The Foster of the late 80’s and early 90’s was a much better hurdler than the Foster of the late 70’s and early 80’s. He tightened up his arm action, he tightened up his lead leg action, he stopped ducking his head down, and became an overall much more efficient hurdler. Despite losing to Roger Kingdom in the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, Foster remained king of the World Championships (which were held once every four years back then), as he won two more World Championships — in 1987 and 1991. The 1991 WC final was, in my opinion, the best race of his career, even though the time, 13.06, was .03 slower than his time against Nehemiah. In 1981, Foster was a monster competitor. By 1991, he was a master hurdler. In that 1991 race, he and Jack Pierce ran neck-and-neck from the start line to the finish line. They both finished in 13.06, but Foster was given the victory based on the photo. I always get a chuckle out of the fact that as the two men were celebrating together, Pierce looked none too happy with the second-place finish. I don’t think automatic timing systems went to the thousandth of a second like they do now, so I’m sure he felt cheated. Still, it was a great race to watch, and a great race by both hurdlers.

As I’ve grown older, the idea of how old is “old” gets older and older. From where I’m sitting, 64 seems way too young to die. But I’m glad that Foster is no longer suffering, and that he can rest now.

[/am4show]