Hurdling Relationships

by Steve McGill

When I reflect on my relationship with the hurdles, I can see that it has come to define my life and shape my life in ways that I never could have imagined when I decided to follow my coach’s advice as a sophomore sprinter in high school to give the hurdles a try. Or even in my junior year, when I quit the basketball team in order to devote all my athletic energy and time to finding out how good of a hurdler I could become. For me, hurdling is not just an event in a sport. Hurdling is a world. The relationships I’ve built over the years through the hurdles are ones that I treasure.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

In my senior year of high school, when I spent most of my November in the hospital as I battled a rare blood disorder, the only people who came to visit me, outside of immediate family, were my two track coaches and my two hurdling teammates. That was forty years ago, and I still remember, and I’m still grateful.

Last year, when I became temporarily famous after two of my students organized a GoFundMe campaign that raised enough money to send me to the Super Bowl to watch my hometown Philadelphia Eagles play the Kansas City Chiefs, I heard from many people from my past, as the story made the local news and even the national news, and the TikTok post of one of the students had something like half a million views. One of the people who reached out to me was my old college teammate, Mike Ryan, whom I hadn’t had contact with in over 35 years. In our college days, Mike had been the hurdler I looked up to and competed against most fiercely, as he was a year ahead of me and a much better technician than I was at the time. He contacted me via email, and we emailed back and forth a few times. He sent me a few photos of myself, him, and one of our other hurdling teammates from back in the day, and I found myself getting emotional looking at those photos, reliving those memories.

As a coach, it’s different. Athletes come, athletes go, but you keep on doing what you’re doing. But with some athletes a connectedness occurs, a bond forms, that defies explanation. In regards to that, I think back on the time, way back around 2003, when I went to the track by myself on a Sunday to go over a few hurdles, and one of my hurdlers, who had no idea I’d be there, showed up at the exact same time to do some hurdle work himself. We ended up working out together.

Then there was the time about ten years ago, when one of my former athletes, Keare Smith, who lived in New York, flew down to North Carolina to attend the funeral of his father, who had died unexpectedly at the young age of 47. Keare brought his spikes with him, and I coached him through a workout in the falling rain. We didn’t say a word to each other the entire workout. Just being together in the context in which we had always known each other was enough to convey the love and appreciation for each other that no words could adequately express in such a moment. Despite the sorrow, despite the gravity of the occasion, I’ll always remember that day as a beautiful day.

Then there’s Cameron Akers, to whose memory I’ve dedicated my life since the day he took his life in February 2012. Cameron was the first national-caliber athlete I ever coached, and we remained close to the end of his life. I miss him every day. My avatar on my YouTube channel and on my Instagram account is a photo of him, and the T-shirts I give to campers at my Team Steve hurdling academies feature a drawing of the same photo. Cam is my man and he will always be.

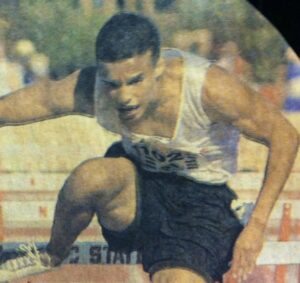

This photo of Cameron Akers appeared in the Raleigh News & Observer in June 2000, at the Adidas National Championships at North Carolina State University. Cameron competed in this meet at the end of his junior year of high school, which was also his first year running track.

When you coach someone, you become that person. I’m talking about the real ones, who put in the work, who devote themselves to the hurdles. You become that person because you have to enter their world in order to coach them, in order to give them what they need from you. It’s something that happens gradually, over time, without any intent involved. The more time you spend with the person, the more you appreciate the fullness of their personality, and the less you feel like you’re the teacher and they’re the student. You also shed the desire to “change” them or improve them in some way. You’re willing to let them be who they are. As that happens, you come to love them for who they are, and then you gradually become who they are, in the sense that your personality meshes with theirs.

As they move past their fears and grow more confident in their abilities, you realize how special it is to be the person who is facilitating that growth. Their growth is your growth, because you had to grow as a coach in order to help them. You had to step outside your comfort zone in order to push them outside of their comfort zone. You had to find something deep within yourself in order to help them find something deep within themselves. It’s beautiful and it’s magical and it’s what makes coaching such a wonderful calling, because you can never coach any two athletes the exact same way. Each individual’s uniqueness has to be honored, all the baggage they come has to be embraced, if the magic is to occur, if the relationship is to become sacred, and if the athlete is going to achieve their potential.

I’m grateful for every athlete I’ve ever coached. Especially the ones who gave it all they had, regardless of talent level. Have you ever heard of David Jones? Joe Coe? Alex Steinbaugh? Caroline Pyle? Nia Brown? Garrison Rountree? Kobi Johnson? These are just a few names of hurdlers I’ve coached whom I appreciate and miss. None of them went on to win NCAA championships or qualify for Olympic teams or set world records. But all of them gave their all to the hurdles.

The time we spend together in this hurdling world is but a blip in our lives. It comes and it goes. That’s why we must value and treasure that time, and give all of ourselves to each other in each moment.

[/am4show]