The Jazz of Hurdling

“I believe that men are here to grow themselves into the full – into the best good that they can be. At least, this is what I want to do. You know? This is my belief, that we are supposed to – I am supposed to grow to the best good that I can get to.” –John Coltrane

Introduction

On the surface, jazz music and hurdling seem to have very little in common. And comparing the two might appear to be a bit of a stretch. But for me, jazz and hurdling go hand in hand; the connections are many and obvious. I have learned more about hurdling and coaching hurdlers from listening to jazz than from any other source. Largely, that has to do with jazz music’s heavy emphasis on individual expression and improvisation. The greatest lesson that jazz teaches is that there is never any end to exploration; you can always learn more, you can always find ways to improve, there is always room to grow, no matter how much you have accomplished. The more you know, the more there is to know. The more you think you know, the more you realize you don’t know anything.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

Sound

“I recognize the artist, and I recognize an individual. I see his contribution; and, when I know a man’s sound, well, to me that’s him, you know, that’s this man.” -John Coltrane

I can’t point to a specific moment when I first heard jazz. That’s because, growing up as a little boy, I heard jazz all the time, before I even knew to distinguish it from other types of music. My dad played jazz records in the house all the time. He had spent much of his young adulthood in the 1940’s and 1950’s in Philadelphia, frequenting clubs where jazz legends performed on a regular basis. In the last year of his life in 1997, he told me many stories about watching live performances that featured the likes of trumpeters Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, and Louis Armstrong, singers Sarah Vaughn, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday, saxophonists Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, and John Coltrane, and there were dozens of other names that came up in conversations.

My dad’s love of jazz was on a level of my love for hurdling. Dad would always point out that every notable musician had his own “sound,” just like I always point out that every notable hurdler has his own style. Dad said that the most important aspect of being a jazz musician involved developing one’s own sound. Coming up through the ranks, a musician first had to master the things that more established musicians were doing. It was important to learn the vocabulary, to become fully acquainted with your instrument. At first, your sound is comparable to the sound of older musicians and/or to contemporaries. But after a while, if you’re going to make a mark on the music, if you’re going to move the music forward, if you’re going to leave your own imprint on the music, you have to find your own sound. And the only way to do that is to form a bond with your instrument, to take risks, to experiment and explore, to go beyond the known and face the unknown.

But as a kid growing up, I wouldn’t have understood any of this. All I knew back then was that jazz music sounded very weird. My oldest brother and my sister listened to soul groups like the Isley Brothers and Earth Wind & Fire. My other brother liked rock music. Being the youngest, I was influenced by everyone’s tastes. I just remember that when dad would put some Thelonious Monk or Dizzy Gillespie on the record player, I would whisper to one of my siblings, “Why does dad keep playing that stuff?”

Not until I was in my 20’s did I start to listen to jazz more closely, and begin to hear the “sound” of individual musicians. The reason I began to listen more closely was that I finally started to realize that the musicians were communicating through their instruments instead of communicating through lyrics. Before, I couldn’t tell a trumpet from a saxophone. But now I could hear the things that certain musicians did that distinguished them from others. Louis Armstrong, Clifford Brown, Miles Davis, and Dizzy Gillespie all played the trumpet, and they were all masters of the instrument, but none of them sounded the same. Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz, and John Coltrane all played the tenor saxophone, but it was easy to tell who was who within the opening notes of a tune.

Funny thing is, my deeper understanding of jazz music first arose at one of the rare periods of my life when I wasn’t involved in track at all. I was in graduate school taking literature classes, reading obscure fiction and writing papers all day long. I had already accepted the fact that my hurdling days were behind me, and that it was time to move forward with my academic life and career options.

While studying, I would listen to jazz. I preferred music over silence, and jazz was more effective than other types of music because there were no lyrics to distract me. But what I discovered with jazz was, instead of the music distracting me from the studying, the studying was distracting me from the music. I was hearing things in the music that caught my attention. Little things. A brief musical conversation between the piano and the bass, a subtle shift in mood during a saxophone solo, the way certain drummers could push the music to new levels of intensity without needing to solo. No longer did all jazz sound the same to me. I had my own favorites. There were particular musicians whose sound stood out to me, whose sound made me feel and think more deeply. Often I found myself closing the book I was reading, putting down my pen and highlighter, and listening.

This notion of having a “sound” began to make sense to me. And oddly, listening to this music, especially that of the John Coltrane Quartet, made me think of the hurdles. Coltrane had a sound. He didn’t play like anybody else. I found myself thinking that I had never reached that point as a hurdler, where I had my own style. And I found myself wondering how does one reach that point as a hurdler? Throughout my years as a collegiate athlete, I had studied the hurdles religiously, studied the styles of great hurdlers of the time (Renaldo Nehemiah, Roger Kingdom, Greg Foster, Tonie Campbell, Colin Jackson) and of the past (Rodney Milburn, Guy Drut), I had read plenty of articles on hurdlers in Track & Field News, I had devised my own workouts, studied the styles of my opponents. Everything I learned, I tried to incorporate into what I did. But I had never reached a point where I could say this is how I hurdle. Still, I had felt, on occasion, in a handful of workouts and races in which the rhythm was right, a sense of identity running the hurdles. A feeling that I wasn’t just running the hurdles, but that I was a hurdler. Hurdling was my art form, my means of self-expression, my way of showing people who I was. But I never had a chance to build upon those brief glimpses. The season was too short, and I wasn’t good enough to qualify for nationals.

And now that I was done with college, done with hurdling, with all my eligibility used up, I didn’t just miss hurdling; I missed being a hurdler. I missed the journey – the inner journey of discovering more and more about myself through hurdling.

The urge to continue that journey is what ultimately led me to coach. Practically speaking, as someone with a master’s degree in English, with no prior background in fields of study that would lead to coaching, I was planning on just teaching. But at the high school level, teachers are often asked to coach. So being an assistant with the track team was a natural fit.

Coaching hurdlers, I quickly learned, is all about coaching the individual, because each hurdler is an individual. When I first started coaching, I coached all my hurdlers the same way I had coached myself. I had them do the workouts I had done, and I taught them to clear the hurdles the way I had cleared them. But I soon discovered that that approach didn’t work. Hurdlers are finicky like cats. Hurdlers are very cerebral, prone to getting bogged down in their own minds, over-thinking, over-analyzing. Really, ideally, each hurdler should have his or her own lane on the practice track. One hurdler might need to practice with the hurdles lowered, another might need to work on the start, another might need to do a quickness drill, another might need to five-step in between to work on sprinting. Every hurdler has his or her pet workout. My favorite back in the day was the quick-step workout with the hurdles eight yards apart. Some hurdlers I’ve coached hate that workout. Some master isolation drills the first time they do them; others never get the hang of such drills. Etc., etc.

And when it comes to styles, some hurdlers are very powerful, others are very fast, others are very quick, others are very flexible, many are some combination of the above. Mentally, some are perfectionists, others get easily frustrated, others ask tons of questions, others want you to tell them what to do, some take a football approach, others constantly need a pep talk.

So in developing a style, in developing the equivalent of the jazz musician’s sound, all these factors come into play. Body type, personality, favorite workouts. Being a student of the event is extremely important. Ironically, however, being too much of a student can also impede a hurdler from finding his or her own style. And this is the paradox. In order to find your own sound, you have to digest the sounds of all the masters who came before you and of all the peers who surround you. In order to find your own style, you have to digest the styles of all the hurdlers who came before you and of all your competitors. The only way to find your own style is to study all these other styles while in the process of developing your own. You don’t find your own style by ignoring everyone else and just focusing on yourself.

The danger lies in trying to mimic the styles of others. I’m reminded of one of those old Bad News Bears movies from back in the day about the sorry little league baseball team. In one scene, a pitcher for the Bears was trying to pitch like all of the professional pitchers that he admired. Before throwing the ball he would name the pitcher that he was impersonating. But each time he pitched, the ball didn’t even reach home plate. Finally the manager walked out to the mound and told him, “Just throw the damn ball.” The kid followed this advice and hummed a fastball that whizzed past the batter for a strike. The kid looked over at his manager and smiled as if to say, “Oh, that’s all I had to do?”

Many hurdlers get caught up making the same mistake. They’re hungry to run faster, so when they see somebody running fast, they try to mimic what that hurdler does without really understanding and fully digesting what that hurdler is doing. The Aries Merritt lead arm style serves as a good example. People see Aries running fast so they adopt that wide sweep of the arm. Even Aries himself needed many years to refine it to execute it with peak efficiency. The 7-step start is another example. I’ve already seen high school girls 7-stepping at indoor meets this year. And no, they don’t look like Dayron Robles.

Hurdlers who are the true students of the event are in most danger of this mimicking pattern. I remember several phone conversations I had with Wayne Davis (2013 NCAA 110H champion, profile subject of the September issue) last year in which he was talking about the styles of Colin Jackson, Dominique Arnold, Robles, Liu Xiang, David Oliver, Milburn, and others. Wayne would watch a YouTube video, see a technical innovation, and try to implement it in his next workout. He was always trying something new. Finally, in one conversation I pointed out to him, “Wayne, I know it’s important to know what everybody else does, but what do you do? What’s Wayne Davis’ style?” It’s a thought I wanted to plant in his head even while aware that, for someone his age, studying the masters is still essential. Really, both are true – there’s no end to the learning, but the learning must be coupled with an ever-increasing awareness of one’s own style. In short, you have to know who you are as a hurdler.

***

Improvisation

“I have no fear about my music being too way out. You are not going to find something new by doing the same thing over and over again. You add something new to the old. You have to give up something to get something.” -John Coltrane

So there’s another paradox. You can never “know” who you are as a hurdler, because who you are as a hurdler is constantly evolving. With every workout you’re making adaptations and adjustments. So it is quite possible to have a style even as you’re developing your style, just as a musician can have a sound even while developing a sound. Life is growth; stagnation is death. There is no “right” way to hurdle. There is no wrong way to hurdle. There are things that work and things that don’t. There are things that are efficient and things that are inefficient. And there is no one size fits all. A lean that is perfectly deep enough for a 5-2 female hurdler may be too deep for a 5-6 hurdler. There could be two hurdlers on the same team with the same coach who both experiment with 7-stepping to the first hurdle; for one it’s the appropriate choice and for the other it would be a disaster.

My thing is, don’t be afraid to experiment. Incorporate what works, discard what doesn’t. Don’t do something just because everyone else is doing it, but don’t not try something just because nobody else is doing it. When inspiration rises, go with it and see where it takes you. In jazz music, this concept is referred to as improvisation. It’s a word I’m sometimes hesitant to use because of the negative connotations associated with it, and the falsely positive connotations as well. In both cases, it is interpreted as having the freedom to “do whatever you want.” No. It’s not about doing whatever you want. Improvisation is not chaotic, it is not random. It does not come from out of nowhere, but from a place very deep within you. Even while the conscious mind is operating on the surface, the deeper layers of consciousness remain at work, working through problems that may lead to new breakthroughs, insights, and solutions.

In jazz, improvisation primarily occurs doing solos. The instrumentalist deviates from the melody in order to express himself more fully. He doesn’t necessarily know where he’s going to go during the solo, but he knows that he will eventually find his way back to the melody. As a listener, you have to be willing to go wherever the soloist takes you, even if all connection to the melody seems lost. In jazz, the aim is not to master a tune, but to continually re-invent a tune, to make it new every time you play it.

The John Coltrane Quartet, for example, played the pop song “My Favorite Things” hundreds of times over the course of their five years together (1961-1965). The studio recording is fairly straightforward, and even the improvisational elements are rather tame. But as the years progressed, the Eastern influence became more evident, the solos became longer, and the song as a whole sounded more like an Indian raga than a fun little ditty from a movie. Coltrane sounded more like a snake charmer than a saxophonist.

For Coltrane, it was all about having a plan, purposefully deviating from the plan, incorporating things he and the band had practiced, totally fearless in the face of potential failure.

But even in jazz there are limits to how far most musicians will go. As with any creative endeavor, once people find a formula that works, they’ll stick to that formula, and look for opportunities to be creative within that particular framework. As music critic John S. Wilson points out, “For all their theoretical sense of freedom, jazz musicians have a tendency to be surprisingly hidebound. As a rule, they find their mode of expression early in their careers. After that … basically the adventure is over” (Kahn 8). As Coltrane himself noted, even he was very cautious early in his career about taking musical risks: “I stayed in obscurity for a long time. I saw so many guys get themselves fired from a band because they tried to be innovative that I got a little discouraged from trying anything different” (Kahn 16).

In poetry, to use another analogy, there was no such thing as “free verse” until Walt Whitman came along in the mid-19th century with his free-flowing style that he featured in his magnum opus, “Song of Myself,” as well as in many of his other poems. Prior to Whitman, poetry was all about rhyme scheme and meter. Everything had to fit within the meter, and the rhyme scheme had to be consistent. Some poets would experiment with different meters, different rhyme schemes, different modes of punctuation. But Whitman came along and blew the roof off the whole joint. The heck with rhyme scheme, the heck with meter. He wrote in long, expansive sentences, verses, phrases, and clauses that would go on for pages. Yet and still, his poetry was very musical, very rhythmic, very percussive. By exploring, by improvising, by deviating from accepted norms and standards, he found a new way to write poetry, he found his own unique voice, and has gone on to be considered one of the greatest poets who ever lived. He is required reading in schools and has been imitated by generations of poets since his time. The “Beat” poets of the 1950’s basically created a whole new sub-genre of poetry that was rooted in Whitman’s influence.

The difference between a Coltrane, a Whitman, a Miles Davis, and the usual artist is that they ignore the Dead End sign at the end of the road. When most artists get to the Dead End sign, they stop, turn around, and continue to function in the world of normalcy. But the work of the true improviser begins at the Dead End sign. They go forward where all others turn back. They innovate. They discover new modes of expression that go on to become the new norms, the new standards. As Coltrane once said, “…these innovators always seek to revitalize, extend and reconstruct the status quo in their given fields, whenever it is needed” (Brown 8).

In any art form, in any field of endeavor, improvisation rarely leads to innovation. Most improvisation takes place within the context of commonly accepted, established structures. More on that in a bit. In hurdling, I can think of two examples of true innovation: Coach Wilbur Ross with his critical zones approach to the 100/110 meter hurdles, and Edwin Moses with his 13-step stride pattern all the way around the track in the 400 meter hurdles.

Let’s talk about Moses first. Though he wasn’t the first hurdler to 13-step all the way (Wes Williams was), he was the first to master this approach and to run sub-48.00 on a consistent basis with this stride pattern. Moses’ 13-step stride pattern revolutionized the event. To this day there are very few hurdlers who can do it for a whole race, and it is still considered the standard of stride pattern excellence.

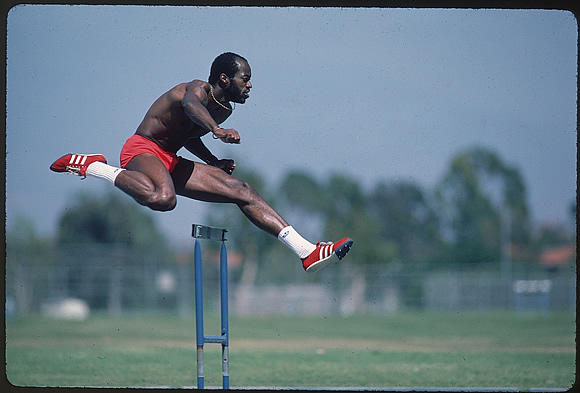

Edwin Moses, master of the 13-step stride pattern.

Edwin Moses, master of the 13-step stride pattern.

As for Ross, I’m not sure of the origins of the critical zones approach, but it too revolutionized the event, and it too remains a fundamental frame of reference. For those of you who don’t know, Ross basically broke down the race into three “critical zones” – from the start line through the third hurdle, then hurdles four through seven, then hurdle eight through the finish line. The first zone is the equivalent of the 100 meter sprinter’s drive phase, the second zone is the peak speed phase, and the third zone is the deceleration/maintenance phase. By breaking down the race into these zones, he was able to design workouts and measure efficiency in each phase of the race. To this day, hurdle coaches and hurdlers at all levels still employ the methods that Ross developed way back in the 1950’s. David Oliver’s coach, Brooks Johnson, is a big believer in Ross’ methods, and has used them in helping Oliver to become a world champion.

In the more day-to-day context, improvisation doesn’t usually lead to innovation, but it can certainly lead to more efficient, more fluid hurdling. If you’re talking about practice, I would define improvisation as making changes in the original workout plan as the moment dictates. I have never had a problem with sharing workouts with other coaches, and that’s for two reasons. One, I don’t believe in the idea of having “secrets,” and I don’t like to be competitive in that sense. If I know of workouts or drills that can help you in coaching your athletes, I’ll willingly pass them on. It’s all in the spirit of helping the athletes improve. Two, I know that having good workouts is the comparatively easy part; the hard part is the actual coaching on the track. The ability to improvise is an essential quality of good coaching.

For example, what do you do with that beginning hurdler who you had planned to have do a series of reps over five hurdles if he or she keeps running up to the first hurdle and stopping? If you don’t know how to improvise, you’ll get annoyed with the kid and blame him or her for the workout failing. If you can improvise, you’ll devise ways to help the athlete get over the fear. He or she might end up never getting over all five hurdles that day, but that doesn’t mean progress can’t be made.

Such types of situations pop up every day on the practice track, at all levels. To me, a workout plan is like a road map: it serves as a guide, but if circumstances force you to deviate from the plan, you have to be ready to come up with new ideas on the fly. And I believe that this is where most coaches of hurdlers fall short – they don’t improvise; they stick to the script even when the script isn’t working. They’re afraid of making mistakes. In my mind, there’s no such thing as a mistake. Even if an idea doesn’t work, it opens up possibilities for new drills or workouts, or variations on old drills or workouts. You always need to be making subtle changes and subtle adaptations to fit the individual athlete. If you keep doing the same old thing you’ll keep getting the same old results.

***

Attention

“When a man’s faith is never tried, I don’t think he’ll ever learn anything. You have to have trial and tribulation, or what are you going to learn? There has to be some adversity for you to know that you have the right tools, if you are equipped to make it.” -McCoy Tyner

To a very large degree, hurdling is all about frustration management. At all levels – from beginners on their very first day to Olympic medal hopefuls, the quality of a training session and the ability to progress in the event is enormously dependent on how well you can manage frustration. In the hurdles, the mental challenges never stop coming. Every time you fix one flaw, another one crops up. When you finally get your speed to where you want it to be, you discover that it throws off your timing. You had your start down just perfect a couple days ago, but today you’re popping up too soon and can’t seem to get good momentum going into that first hurdle. Why? What am I doing wrong? What was I doing before that I’m not doing now? Why can’t I get this? What’s the matter with me? The self-doubt floods in and you feel like a kindergartener learning your ABC’s. You wonder what made you think you could ever be a good hurdler to begin with.

Such inner dialogue is an everyday occurrence for hurdlers all over the world. It’s not just you. I always tell my hurdlers to keep their analytical minds active during training sessions. When you make mistakes or when things just aren’t clicking, don’t react emotionally; figure out what you’re doing wrong and figure out what you need to do to correct it. Every mistake is a learning opportunity; every bad rep can open the door to a good one. If you can’t figure out what you’re doing wrong on your own, then ask your coach between reps. Seek feedback. Troubleshoot. Don’t get upset; don’t react emotionally. It doesn’t help. It’s inefficient. When you react emotionally, you inhibit your own ability to solve the problem, you hinder your own development.

We live in an immediate-results world, we live in an impatient world. We try something new, we want it to work instantly. But the hurdles are not an immediate-results event. The hurdles require patience, persistence, calmness in the face of difficulty and adversity. I was working with a beginning hurdler today, a sophomore in high school, who I just recently introduced to the starting blocks. With beginners, I’ll teach the block start fairly late, since it is such a distinctive part of the race, presenting its own unique set of challenges. So the girl, who has been working on her start a couple times a week for the past three weeks, was still having trouble getting to the first hurdle with the same consistency and same speed that she had when approaching the hurdle from a standing start. By the second rep she declared to the world, “I hate blocks!”

I took her aside and explained to her what she was doing wrong. “You’re not driving,” I said. “Your arms are low, your not driving through your hips, you’re fixated on the hurdle. But the problems aren’t technical, they’re mental. You’re not being aggressive. You’re so scared of not reaching the hurdle that you’re not attacking. Be aggressive out of the blocks the same way you’re aggressive from a standing start and you’ll be fine.”

There wasn’t an immediate transformation in the next rep, but there was improvement. And after a while she was looking very good coming out of the blocks and to the first hurdle. So good, in fact, that I was able to add a second hurdle so she could work on her transition to hurdle two, and that went fine as well. I was proud of her. She didn’t let her frustration get the best of her. As a result, she had a good practice.

For a hurdler, it’s all about reps. With the girl I was just talking about, for example, I didn’t get excited when she finally did a good rep. Instead I told her, “This is our new normal. This is how we do.” I wanted her to get in two good reps in a row. Three in a row. Four in a row. Five in a row. Ingrain the good. Ingrain the efficient. Ingrain that which increases confidence. Pay attention to what you’re doing. Know what you need to do to have a good rep. Before every rep, remind yourself of what you need to do to have a good rep. Stay focused between reps, not just during reps. Keep your mind engaged.

This ability to focus, to pay attention, is something that can be developed by listening to jazz. I contend that all hurdlers can benefit from listening to jazz, whether they “like” jazz or not. Listening to jazz increases your attention span. I remember going to a McCoy Tyner concert about five years ago. Tyner, a brilliant pianist who played with John Coltrane’s classic quartet in the 1960’s and has since gone on to make his own indelible imprint on the music world over the past 4-plus decades, was performing with his own quartet at a local college. Although in his seventies and not in the best of health, Tyner was still a monster on the keyboard, and each member of his band was a musical master as well.

They played for a little over an hour, about five songs, each one over ten minutes long. In jazz, for a song to last more than ten minutes is quite common, especially in live performances. During that concert, I found that I really had to pay attention. There was so much going on. I always felt like I was missing something. If I just focused on the horn player soloing, I would miss what Tyner was doing. If I just focused on Tyner, I would miss what the drummer and bassist were doing. I had to listen to the music as a whole, I had to pay attention to how the musicians were interacting with each other, I had to follow the conversation they were having with each other. At times I had to close my eyes so I could listen better and not get caught up watching. Each solo was an artistic statement, a purposeful expression. They weren’t just “jamming”; they were communicating with each other, and with the audience. I remember feeling tired at the end of that concert because it had required so much of me. This music wasn’t intended to entertain; it was intended to educate. My body wasn’t dancing, but my spirit was, and my mind was actively engaged the whole time. What a powerful experience.

There is very little in our everyday lives that teaches us to pay attention in such a manner. In our modern world we are taught the opposite – we are taught to be distracted; we are taught that being distracted (multi-tasking) is a good thing. So what ends up happening is you do four things at once but don’t give your full attention to any of them, so the quality of your work suffers across the board. We are also taught to expect, even demand, immediate results. Your flowers aren’t growing? Buy some Miracle Gro. Your stomach’s not flat? Do this 8-minute ab routine. You don’t feel like preparing a meal? Grab a burger and fries on the way home. Your wife just ticked you off? Divorce her.

But the truth is, growing a flower requires a lot of tedious grunt work. You gotta keep digging the weeds. You dug them out last week? Well they grew back; dig them out again. If you want to get a flat stomach you have to do all kinds of abdominal exercises daily, and you have to eat healthily, and you need to do cardio-based exercising as well. A good, home-cooked meal that provides necessary nutrients takes time to prepare; it doesn’t come hand-delivered from a drive-thru window. A good relationship requires a lot of listening, a lot of give and take.

So, the reality is, anything of value requires attention, requires patience and persistence, requires the ability to manage frustration. I know that when I listen to jazz, whether I’m at a concert or playing some Coltrane on the iPod during a run through my neighborhood, my anxiety level diminishes, my mental clarity increases, and my spirit soars. One of the things I relish about jazz is that it’s a type of music that acknowledges that the world can be chaotic. In the middle of a solo the musician may have strayed so far from the melody that you can’t even remember what song you’re listening to. Musicians like Coltrane, Tyner, Eric Dolphy, etc. take you places you wouldn’t willingly go yourself. But when you come back to the melody, when you hear that note that announces we are on our way back home, you realize that the journey was worth it. You realize that there’s a reward that comes with staying attentive, with staying calm and staying focused, with trusting the moment every moment.

And to me, this is the connection; this is what jazz and hurdling are both all about at their center: trusting the moment every moment. Staying attentive. Sacrificing immediate gratification for the sake of long-term fulfillment.

***

Vesica Piscis

“The greatest legacy John Coltrane left us was his belief that it is worth the effort to raise whatever we do from the earthly level to the spiritual.” -Aaron McCarroll

When sport aspires to the level of art form, a transition occurs. No longer is the competitive element the only focus, or even the primary focus. It becomes a means to a greater aim – that of self-expression and self-discovery. Very early in my hurdling life – back in my freshman year of college – the thought occurred to me that what I was doing was as much of an art as painting or writing or any other artistic endeavor. I was devoting great amounts of energy to mastering a craft. Yes, winning still mattered very much to me, but mastery of the art form became an equally compelling motivation. My mission with each hurdle workout and each race was to come closer and closer to that feeling of complete harmony, complete rhythm in motion.

As a hurdler, when you realize that what you are doing is indeed artistic in nature, it frees you, at least to some degree, from the ups and downs that come with winning and losing. Win or lose, your focus is not only on the result, but also on the feeling. You understand that if the feeling is there, the results will follow naturally. And it’s not something you need to be loud about, it’s not something you need to profess from the rooftops. You can look the same outwardly and behave the same as usual, but inwardly you know you’re onto something different.

Our society is so obsessed with competition, so obsessed with winning, that it is very difficult for an athlete to function on the level of an artist. When you see photos of former NBA greats Bill Russell and Michael Jordan wearing all their championship rings on their fingers, you know that Russell and Jordan are being celebrated for their achievements, not for the work habits that enabled them to reach such achievements. You are made to envy them for their success, and to wonder why you’re such a failure in comparison. That may not be the intent of the advertisement (or maybe it is), but that’s what happens. We all know there are no championship rings handed out, no gold medals handed out, for mastering an art form. They’re given for defeating the competition. So, to approach your athletic endeavor with the mindset of an artist requires a conscious mental shift. You’re seeking an inner reward, one that this world cannot quantify.

Michael Jordan and Bill Russell, in full bling mode.

Michael Jordan and Bill Russell, in full bling mode.

If you keep moving in that direction – away from the rigidly competitive, toward the artistic – eventually, another shift occurs. You start to realize that, through hurdling, you’re not merely expressing yourself, but that you are expressing your Self. Hurdling, at this point, is not just a competition, and it’s even more than an art form; it is an expression of the divine being that lies within you, at your deepest core.

Again, this line of thinking is Whitmanesque. In his poetry, he explained to us that the material world and the spiritual world are not separate, and that one is not greater, or more valid, than the other. In jazz, Coltrane took this idea to its heights. He didn’t separate his musical life from his spiritual life. He didn’t play saxophone for part of the day then pray for part of the day. Playing the saxophone was his form of prayer. It was his way of contributing to the spiritual evolution of humanity. As he said himself, in one of his more well-known quotes, “That’s what music is to me – it’s just another way of saying this is a big, beautiful universe we live in, that’s been given to us, and here’s an example of just how magnificent and encompassing it is. That’s what I would like to do. I think that’s one of the greatest things you can do in life, and we all try to do it in some way. The musician’s is through his music” (DeVito 153).

And a hurdler’s can certainly be through hurdling. As Coltrane’s long-time drummer Elvin Jones once said, “We’re all human beings. Our spirituality can express itself any way and anywhere” (Kahn x).

Spirituality, whether it manifests itself through hurdling, through jazz, or any endeavor, is spontaneous. It happens to you. It springs up from within you. It’s choiceless. That feeling you get when you run over a flight of hurdles in perfect rhythm and balance – that is a spiritual feeling brought on through a physical act. The spiritual is the physical and the physical is the spiritual. They are one. There is no choice. Religion is a choice. To be a Christian, or a Muslim, or a Hindu, or a Buddhist, is a choice. But a spiritual experience happens; there is no choice. It’s very important to understand the difference; otherwise it’s too easy to get caught up in ideological arguments that are ultimately pointless because they don’t get to the heart of the matter.

If you truly love to hurdle, you will not be able to explain why you love to hurdle. To anyone, not even to yourself. And if you try to explain it, the words will fall miserably short. If hurdling for you is truly a spiritual experience, then any explanation of why you do it will cheapen the experience. To understand that your body is a spiritual vessel, and that hurdling is a spiritual act, frees you from the self-satisfaction that victory can provide, thereby making you an authentic human being, a gateway through whom the spiritual realm enters into the earthly realm. This is how deep hurdling goes, if you keep going.

A couple paradoxes here. One is that the pathway to the divine is through the most mundane thing imaginable: practice. Plain, simple practice. To find the magical, you must go through the mundane. To find the extraordinary, you must go through the ordinary. Coltrane was as famous for his practice habits as he was for his music. Music critic Nat Hentoff made the following observation: “[Col]trane struck such a spiritual chord in so many listeners that people started to think of him as being beyond human. I think that’s unfair. He was just a human being like you and me – but he was willing to practice more, to do all the things that somebody has to do to excel” (Kahn xxi). He was known for practicing for hours on end. He would fall asleep with the saxophone in his hands. He would practice in the bathroom. He would practice between sets. He would practice before and after performances. Constantly searching, experimenting, solving problems. Constantly seeking out new sounds to play on his horn. He was relentless. As drummer Rashied Ali (who played with Coltrane for two years) once said, “He practiced like a man who had no talent, and he had all the talent in the world” (The World).

That’s what I mean when I say that, for a hurdler, it’s all about getting your reps in. Hurdling isn’t about theory. It’s not about the right way versus the wrong way. Every rep is a new rep, every race is a new race. The past is dead and the moment is all you have. The only way to learn how to hurdle is to hurdle. Address your hurdling questions by hurdling. Be open to all possibilities, and explore all possibilities. Never settle for textbook answers. Practice.

The other paradox is that, for the hurdler, competition is the path that must be traveled if the artistic and spiritual dimensions of the sport are to be actualized. The notion of “Oh, I’m an artist, I don’t care if I win or lose” doesn’t work. And such an attitude would be a gross misinterpretation of all I’ve been saying up to this point. A hurdle race is a foot race, it is a competition, and winning does matter. The athlete has to perform in the fire, in the heat of the battle. The athlete has to stand in front of the starting blocks and stare down that lane of hurdles. The athlete must face the moment; there can be no backing down from the moment. When you face the moment, when you run your race, that’s when you realize you’re a hurdler. That’s when you realize you’re an artist. That’s when you realize that the divine expresses itself through you.

***

Works Cited

Brown, Leonard ed. John Coltrane & Black America’s Quest for Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. Print

DeVito, Chris ed. Coltrane on Coltrane: The John Coltrane Interviews. Chicago: A Capella, 2010. Print.

Kahn, Ashley. A Love Supreme: the Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album. New York: Penguin, 2002. Print.

“The World According to John Coltrane.” Masters of American Music. Bmg Special Product, 2002. DVD.

Other References

The opening epigraph of the essay is from Coltrane on Coltrane, page 277.

The opening epigraph of the “Sound” section of the essay is from Coltrane on Coltrane, page 283.

The opening epigraph of the “Improvisation” section of the essay is from Coltrane on Coltrane, page 222.

The opening epigraph of the “Attention” section of the essay is from A Love Supreme: the Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album, page 46.

The opening epigraph of the “Vesica Piscis” section of the essay is from the article entitled “Spiritual Improvisation” that appeared in the July-August 1999 edition of Sojourners Magazine. http://sojo.net/magazine/1999/07/spiritual-improvisation

[/am4show]