Ankle Sprains

Ankle sprains, like groin strains discussed in the April issue of The Hurdle Magazine, are more common in sports that require a good deal of lateral movement than they are in track and field. Many basketball, soccer, and football players have their ankles taped prior to every practice and competition. In track, that same tape is more often used for marking relay take-off spots than it is for injury prevention.

But there are events in track and field that, despite the lack of lateral movement, demand much lower leg strength and ankle stability. We’re talking about the pounding events, the ballistic, plyometric events. Namely we’re talking about the high, long, and triple jumps, the pole vault, and the hurdles. Sprinters too need strong ankles, since a great amount of force is applied to the track with each stride.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

In the hurdling events, the sprinter’s force is multiplied with each push off of the trail leg and each touchdown of the lead leg. Strong ankles help hurdlers to “run off the hurdle” without dropping their hips. They help hurdlers to push into hurdle position in an explosive manner. In short, if your ankles can’t support your weight, you can’t run the hurdles.

Podiatrist Kelsey Armstrong – The Hurdle Magazine’s expert when it comes to all things injury-related – agrees that hurdlers are particularly susceptible to ankle ailments. “The hurdling motion,” he says, “with a resultant foot touchdown necessitates a stable ankle joint complex, regulated by multiple factors. If this stability is not there during touchdown, the structures supporting the ankle will break down.”

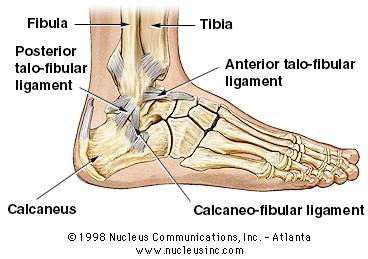

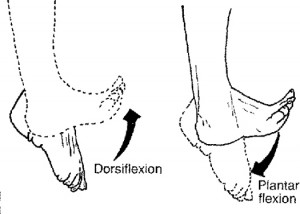

As with terms like “groin strain” and “shin splints,” “ankle sprain” is a catch-all term that oversimplifies what actually occurs. According to Dr. Armstrong, “there are three ligaments on the outside of the ankle which are commonly involved in ankle sprains. These ligaments connect the fibula (leg bone) to foot bones (calcaneus or talus). They are most likely to be stressed when the foot is in a position of tilted inwards (inversion) and toes pointed downwards (plantaflexion). The severity of the ankle sprain depends on the damage to these ligaments, ranging from ligamentous ‘pull’ (Stage I) to complete tear of all three ligaments (Stage III).”

Dr. Armstrong’s insights indicate that proper running mechanics – sprinting with the ankles dorsi-flexed and the toes pulled up so that each stride lands on the ball of the foot – can go a long way in preventing ankle sprains.

***

Over the years, I’ve had several hurdlers who showed promise but had to drop the event because their ankles couldn’t stand the pounding. Over and over, they’d suffer minor sprains that would keep them out for a week, until finally we came to a mutual agreement that their body just wasn’t going to allow them to hurdle.

In almost all such cases, these athletes came from sports like football or basketball that required constant cutting, jumping, stopping and starting, and shifting of direction. So they came to the hurdles already having suffered ankle sprains in the past. Dr. Armstrong says that this not uncommon at all.

“There are many contributing factors to ankle sprains,” he says, “but the most common is previous ankle sprain. The initial damage can cause decreased muscular strength around the ankle joint, decreased body awareness (proprioception), stiffness in the ankle joint range of motion (osteoarthritis, bony growth, etc.), and most importantly, weakness in the hip and core musculature. All these factors can be present, even though the athlete feels healthy.”

So as a coach scoping out potential hurdlers, it will help to ask the athlete about his or her injury history. A football player who racked up a lot of yards on the field, for example, might seem like a perfect candidate to run the hurdles. But if he has a history of ankle sprains, or even if he’s had just one, then chances are he won’t be able to hurdle without reinjuring himself. The earlier injury has decreased the range of motion in the joint – range of motion that is essential to executing the hurdling action effectively.

Armstrong notes that the intensity of the activity is another significant contributing factor to ankle sprains. “There will be a higher chance of an ankle sprain during the competition versus practice and during speed sessions versus easy tempo runs.” Yet when it comes to hurdling, the intensity level is always going to be relatively high, even when doing drills at slower speeds, for the simple fact that you have to get over the hurdle. And because hurdling requires so much repetition, volume becomes a factor as well. But yes, as Dr. Armstrong suggests, the faster you’re moving, the more force you’re applying. And the more force you’re applying, the greater the risk of an ankle sprain. Still, my experience has been that hurdlers who have efficient sprint mechanics and who have no prior history of ankle sprains have had no ankle problems even when moving at high speeds.

The point Dr. Armstrong makes about weakness in the hips and core is worth addressing in more detail. If a previous ankle injury can lead to weakened hip and core muscles, then the reverse is also true: weakened hip and core muscles can lead to an ankle injury. “If there are weak hip muscles and core muscles,” Dr. Armstrong says, “the position and forces that cause ankle sprains will dominate.” In other words, hip stability and core stability go hand in hand with ankle stability. And “maintenance of ankle stability is vital during hurdling.” Dr. Armstrong suggests that hurdlers with weak ankles should include squats and deadlifts to their weight program to strengthen the hips and to activate the core.

***

Stage I and Stage II ankle sprains can be treated with the traditional RICE treatment (rest, ice, compression, elevation). This treatment should be supplemented with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) such as Motrin. The NSAIDS can be taken orally (a pill) or topically (a cream).

But while this old-school method still works, Dr. Armstrong says that “the standard of care has shifted [from RICE] toward bracing and progressive weight-bearing exercises as tolerated, as it has shown quicker results.” This is what Armstrong has been using, “along with a topical formulated NSAIDS cream.” With this treatment, the return to activity ranges “anywhere from five to fourteen days,” depending on the athlete. In addition to weight-bearing exercises, Armstrong also suggests balance training and range of motion exercises prior to returning to training.

A Stage III ankle sprain requires a much more intensive recovery plan over a longer period of time. First, the ankle must be immobilized with a cast for at least ten days. The cast will then be replaced with a brace, and the athlete can do progressive weight-bearing exercises as tolerated.

Upon returning to running, the athlete should keep the level of impact low by doing slower repeats and by avoiding harder surfaces. The athlete should be able to run pain-free on grass before running on the track. When it comes to hurdling, the same rules apply. Start with the hurdles lower and spaced more closely together before graduating incrementally to race height at high speeds. The key to coming back successfully from an ankle sprain is to listen to your body and to allow each day to build on the next.

To prevent ankle sprains, it’s best to strengthen the ligaments around the ankle and to maintain the range of motion on a regular basis. For strengthening, skipping rope (keeping both feet together) and plyometric exercises such as single-leg bounds can be beneficial. For range of motion, it’s a good idea to include ankle rolls in the pre-workout and post-workout stretching routine.

[/am4show]