Know Your Opponent

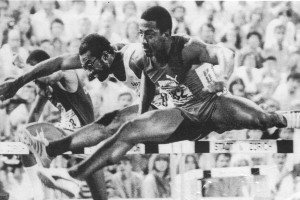

A lot of times in track and field, especially in the hurdles, athletes get distracted and lose focus due to things going on in other lanes. Coaches like to preach, “Run your own race,” but doing so isn’t always so easy. Logically speaking, because the race is run in lanes, no one in another lane can affect what goes on in yours. But of course it is human nature to get caught up in competing. When someone gets ahead of you, it’s easy to fall prey to trying too hard to chase him or her down. When you get out ahead, it’s easy to fall prey to relaxing too soon.

[am4show not_have=’g5;’]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=’g5;’]

While knowing the strengths and weaknesses of your opponent is arguably not as important in the hurdles (or in track in general) as it in team sports or in sports that require one-on-one combat (boxing, wrestling, tennis), it does matter in track, and can aid one’s performance if for no other reason than it can decrease anxiety. As a coach, I like for my athletes to know the strengths and weaknesses of the other hurdlers, and often we will discuss what we need to do to defeat a particularly tough opponent.

The first thing I want to be aware of regarding their opponents is whether they lead with their right leg or left leg. Do they hug one edge of the lane or the other? Do their arms flail when they clear hurdles? This is the first thing because of the possibility of contact during races, which happens much more often than the casual observer realizes. If you’re a left leg lead and Hurdler X from the other team is a right leg lead, and he is in the lane to the immediate left of you, you have to go into the race expecting some contact. If he’s bigger and stronger than you, you might have to make it a point to get out fast to avoid any elbows, hands or forearms coming your way. The most well-known example of contact during a race having a major impact on the results occurred at the 2011 World Championships, where Dayron Robles grabbed the arm of Liu Xiang and pulled him back. Both of them fell off balance, and Jason Richardson ended up capturing the gold. Robles was disqualified, but that didn’t help Liu at all.

Another thing I want to be aware of is who among my athlete’s opponents has a really fast start. Nothing can throw off your timing and your confidence than getting blasted out of the blocks. To compete against someone who has a blazing start can make you quit before you even get going. In such cases, I remind my athletes that the race is over ten hurdles, not one, and there is a finish line at the end. Even though a 110 or 100 meter hurdle race is relatively short, it’s really a long race in the sense that a lot of ebb and flow can occur, and the athlete who gets out first will not necessarily be the athlete who finishes first. Run all ten hurdles.

The battles that occurred between Liu and Terrence Trammell in the mid-2000’s depicted this point perfectly. Has there ever been a faster starter in the history of track and field than Trammell? Hurdles or sprints? But Liu never let those fast starts intimidate him. Nor did he panic and try to make up all the ground at once. Instead, he gradually made up ground over the entire last half of the race. In this case, Liu didn’t just know his opponent’s strength, but he also knew his own. He knew he was a master technician and a strong finisher, and he trusted that his strengths would give him the edge in the end, and they did.

Similarly the Renaldo Nehemiah vs. Greg Foster duels in the late 70’s and into the early 80’s showed the value of knowing one’s opponent. Nehemiah knew that the taller Foster struggled with crowding in the middle and late stages of races, that it grew increasingly difficult to fit in his three strides as the urge to open up his stride grew greater. Nehemiah also knew that Foster tended to hit hurdles more often when running from behind. So Nehemiah would make it a point to beat Foster to the first hurdle and then “listen for the wood.”

If you look at an Allen Johnson, he’s someone who didn’t make mistakes. That’s why he was able to battle with the likes of Liu and Robles into his old age. You couldn’t count on him defeating himself, because it wasn’t going to happen. Roger Kingdom is someone I would describe as another strong finisher. Even if he was clobbering hurdles early in the race, he was coming for you late in the race. You couldn’t just listen for the wood with Kingdom and assume he was out of the picture. He was always going to come back on you.

In the 400 hurdles, if you’re running against a Bershawn Jackson, you know he’s coming for you once you get past hurdle five. He shifts gears at hurdle five, so if you take your foot off gas thinking today must not be his day, you may be in for a rude awakening.

Edwin Moses is known for his winning streak and his gold medals, but he should also be known as the man who elevated the level of competition. Running against Moses, who 13-stepped all the way, opponents knew that they had to do the same thing, or at least come close to it, to have a chance. That’s why, in his era, sub-48’s were relatively common. Andre Phillips, Harald Schmid, and Danny Harris are just a few of the athletes who raised their level of performance in their attempts to take down Moses. Nowadays a sub-48 is as rare as snow in the summertime.

As I mentioned earlier, knowing your own strengths is part of the mix when it comes to knowing your opponents’. Back when I was coaching Wayne Davis II, I would remind him to get out fast and stay in front. Wayne had a great start, and because he was so efficient over the hurdles, most people would quit when they saw him get out ahead of them. And for him, it was always best to run in front, to put the pressure on his opponents to catch him, to pressure them into making mistakes.

Meanwhile, in coaching Johnny Dutch, who didn’t have as fast of a start but was very fluid and rhythmic with his style, I would always tell him, in the 110’s, “No one can beat you over ten hurdles.” And more often than not, that proved to be true.

While we often study our opponents to pick up things they’re doing that we may want to incorporate into our own style, I feel it is equally important to study your opponents so that you can mentally prepare for any specific challenges that those particular opponents may present. At the end of the day, it’s all about getting better, and making each other better, and bringing out the best in each other. That’s what the true spirit of competition comes down to.

[/am4show]