Wayne Davis II: The Record Chaser

“To express yourself, to be unique, to have a unique style, there’s no beginning and there’s no end. It’s an ongoing, never-ending journey. It’s an ocean you never will cross.” -David S. Ware

Introduction

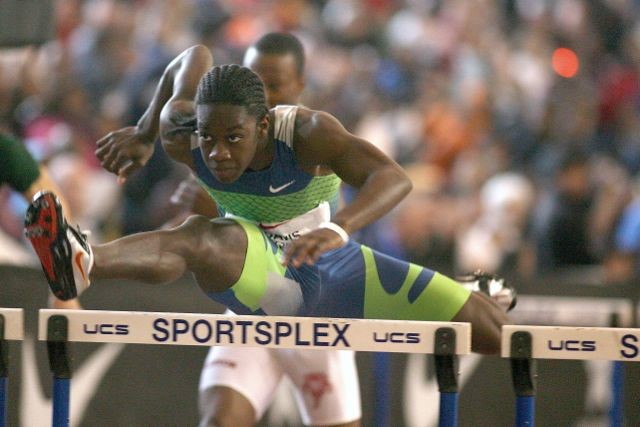

In the men’s 110 meter high hurdles, there’s a common assumption – and with good reason – that if you’re not tall enough, you can never be one of the best in the world. But 2013 NCAA champion Wayne Davis II, at 5-10 ½, has never been one to let common assumptions limit him. As a skinny little nine-year-old boy growing up in Raleigh, NC, he didn’t look like a kid who should try the hurdles, but he tried them anyway. After defying the odds and becoming an age-group champion at age 14, it seemed a good bet that his small stature would catch up to him entering high school, where the hurdles would be raised a whopping six inches, from 33 to 39. But Davis won the Nike Outdoor National Championships in June of 2007, setting a sophomore record of 13.65. He went on to have arguably the greatest high school career ever in the 110 hurdles, winning gold at the World Youth Championships in the Czech Republic in July of 2007 (over 36” hurdles), setting a new 60m hurdle record of 7.60 at the Nike Indoor National Championships in March of 2009, then capping it all off by breaking Renaldo Nehemiah’s long-standing national high school record of 12.9 (hand-timed) with a 13.08 at the Pan-Am Junior Games in his parents’ home country of Trinidad in July of 2009, after the end of senior year.

He was supposed to be too small to make the transition from high school to college. Some major programs shied away from him, despite his enormous success as a prep, believing he had already maxed out his potential. And though he did struggle early on in his career at Texas A&M, he eventually made the necessary adjustments to the big boy barriers, resulting in a 2nd-place finish at the NCAA championships in 2012, and an NCAA victory this past June. Meanwhile, in international competition, he switched allegiances from the United States to Trinidad, representing the small island country in the 2012 Olympics and the 2013 World Championships, making it to the semi-final round in both meets.

Having reached the top at the youth level, high school level, and collegiate level, the world-class level is the next frontier awaiting the young Davis, who turned 22 this past August.

“Demolishing Hurdles Like a Superhero”

Davis was born in Raleigh on August 22, 1991, two years after his parents moved from Trinidad to the US. By the age of five he already had hurdling dreams on his mind. Watching the 1996 Olympic Games that took place in Atlanta, GA, the five-year-old Davis did not know enough about track to be impressed by Michael Johnson demolishing world records in the 400 and 200 meter dashes. Instead, his imagination was captured by another Johnson – Allen Johnson, who smashed and crashed crossbars on his way to a gold medal in the 110 hurdles.

“It looked so exciting to me,” Davis said when I interviewed him in late August, shortly after the World Championships in Moscow. “It looked so fast. He was demolishing hurdles like a superhero. I said, ‘Mom, that’s what I want to do.’ If he’d run a clean race, I probably wouldn’t have wanted to hurdle. I saw him as a monster, as a beast. After that, I started setting up chairs in the house and jumping over them. If I ever got to the track, the hurdles were the first thing I’d look for.”

Davis began hurdling competitively in the summer prior to his tenth birthday. He ran for the Raleigh Junior Striders, under the guidance of hurdle coach Aaron McDougal. His teammates included Johnny Dutch and Keare Smith. Dutch, two years older than Davis, was sort of a big brother to Davis, while Smith, one year older than Davis, was a friend and rival, since they often competed in the same age group. Dutch, who currently runs professionally as a 400m hurdler, was a hurdling god as a youth, and Davis had the good fortune to admire him from up close.

“He was a national champion,” Davis said. “A really big public figure.” With Dutch leading the way, the Junior Strider hurdlers felt unbeatable. “Me, Keare, Johnny, we felt like we had the best coaches ever. We felt like we were always gonna win. Keare and I often came in 1-2. We just knew we had better technique than everybody else.” About Dutch, Davis added, “He was really smooth. Really fluid over the hurdles. His style of hurdling was very unique. In practice I’d see he was faster than me, so I figured I should be doing what he’s doing.”

This habit of observing the tendencies of masterful hurdlers and incorporating their strengths into his own style has been a key to Davis’ consistency and development ever since those childhood days. In the mid-2000’s, when world-class hurdlers could be viewed on YouTube, the main hurdler of choice was 2004 Olympic champion Liu Xiang of China, although there was also Johnson, Terrence Trammell, and then Dominique Arnold. “Whoever was good at the time I watched,” he said.

Davis’ obsession with Liu was largely due to my obsession with him, as I began coaching Davis in his early teens. I had never seen a hurdler as technically precise as Liu, and I often conversed with Davis about the things Liu was doing that no other hurdlers did. As Davis recalled, “We tried to emulate his lead arm, his trail leg, his quickness between, how tall he was between the hurdles, that lean. The lean comes from the hip, the lean is very slight, and it’s gotta be forward. I don’t think I got that back then, but now I’m understanding that.”

As for Trammell, it was his phenomenal start that stood out to Davis. There’s never been another hurdler with as explosive a start as Trammell. He also boasted legitimate world-class 100 meter dash speed, which is a claim most hurdlers, even the best, cannot make. “I saw Trammell as a great sprinter,” Davis said. “I felt that if I could be a faster sprinter, I could be a faster hurdler. I later learned that sprint speed isn’t the same as hurdle speed. But my speed was my weakness. I couldn’t get close enough to the hurdles to where I had to be really quick in between. And his start. He would rocket out the blocks. My senior year [of high school] I watched his start a lot because I was trying to break that indoor record. I realized I didn’t have the strength and acceleration power, and that it would come with time. That’s why I began lifting so hard those days.”

Chasing Records

Davis craves being the best. He loves to chase down records. Yet his quest to break records and set new standards has never caused him to lose focus or perspective. For him, the quest to be the best is an enjoyable, thrilling journey that challenges him on all levels. I can remember when, as a freshman in high school, in his first meet over the 39’s – an indoor meet – he finished second in the final, with Dutch being the only hurdler to finish ahead of him. While his teammates and coaches were celebrating his surprisingly high place, he was lamenting the fact that Dutch had beaten him. At first I thought he was joking. Did he really think he could walk onto the track and defeat Johnny? But when talking to him after the race and looking into his eyes, it became evident that he was serious. The disappointment was real. He was replaying the race in his mind, recalling where he had made mistakes. And I realized in that moment that Wayne had a key quality that all great athletes have –a belief in himself, an unwavering confidence in himself, a certainty that he belongs. And I knew I was in the presence of someone who would go on to do some remarkable things in this sport.

For most athletes, chasing records serves as a distraction, but for Davis, it helps him to focus. “The thing about having a record,” he explained, “is that you can say, at least for that one time, that you’re the best person ever to do this one thing. And if you stop and think about that, it’ll blow your mind. I am literally the best of anyone who’s ever done that. Nobody back in the day, nobody today can beat me. Of all the thousands of people who do this event, I’m the best of all. That is what’s on my mind and that’s one of the reasons I chase records. It’s a good feeling to know I’m the best.”

On his way up the ranks, Davis knocked down records like bowling pins. Meet records, state records, national records, age group records, indoor records, outdoor records. Arguably his most impressive performance came in March of 2009, when, as a senior at Southeast Raleigh High School, he broke Terrence Trammell’s national indoor record with a 7.60 over the 60m hurdles. What was most impressive wasn’t the time, but the fact that he ran the final on a weakened ankle that he had sprained a week earlier while horsing around playing pick-up basketball with friends. In the semi-finals, he aggravated the injury, and could be seen walking around the arena supported by a pair of crutches. He didn’t know for sure if he’d be able to run the final at all. But the next day, he blocked out the pain, allowed his adrenaline to take over, and raced.

Davis on his way to a national high school record in the 60m hurdles. (photo courtesy of www.nationalscholastic.org)

One would think that Davis’ most satisfying race as a prep would be the 13.08 he ran at the Pan-Am Junior Games in July of 2009, when he broke the “unbreakable” record of hurdling legend Renaldo Nehemiah. Nehemiah ran a hand-timed 12.9 in his senior year of high school, which translates into a 13.14 converted to automatic timing. Davis’ 13.08, therefore, is considered faster. And the wind reading for that race was a barely legal 2.0. The perfect storm. Add in the fact that the race took place in Trinidad, in front of Davis’ parents and many other family and friends who were cheering wildly for him, the race marked a storybook ending to a brilliant high school hurdling career.

But for Davis, the most satisfying race took place a month earlier. The race he remembers the most was the 13.16 he ran at the USA Junior Outdoor National Championships. He was a high school hurdler competing against several hurdlers who had completed their first collegiate season over the 42’s. The race was to be run over 39’s, but the odds were still stacked against Davis being able to defeat some of the older, more mature hurdlers he would be facing here. The main rivals included Michael Hancock, a Colorado native against whom Davis had competed against many times in high school; Booker Nunley, whom Davis had trained with and competed against in USATF Junior Olympic track and had just finished his freshman year at the University of South Carolina; and William Wynne, who had beaten Davis every which way but blue in Junior Olympic meets over the years and was now running for the University of Florida.

“Everybody was at their prime,” Davis recalls, “running faster than they’d ever run. Booker and William Wynne were coming out of the collegiate season. I pulled away after hurdle seven. I celebrated after that race, and that was the first time I had ever celebrated after a race. Wynne had beaten me countless times. Hancock was still very fast. So that was a huge win, a huge confidence booster.” Still, some argued, perhaps accurately, that Davis was at an advantage in that race. The older hurdlers had grown used to the higher height and couldn’t contain their speed late in the race, whereas Davis was still used to the 39’s, so his smaller height was actually advantage in this case.

“A Totally Different Game”

While the transition from the 39” hurdles of high school to the 42” hurdles of college is a difficult for any hurdler, it is especially difficult for smaller hurdlers, for whom that three inches can necessitate that they totally revamp their style in order to run fast consistently. When Davis first entered Texas A&M as a freshman, he was admittedly resistant to making changes – an attitude that he says limited his development. He came to realize that college athletes were bigger, stronger, and faster than those he had faced in high school, and that if he was going to compete with them, he would have to get bigger, faster, and stronger himself. And the technical mistakes that he was able to get away with over the 39’s would have to be corrected over the 42’s.

“Hurdling over 39’s is an entirely different race,” he said, “especially because of my height. I had to learn to change, to develop myself into a totally different hurdler. The same old things don’t work over those high hurdles. My coaches (Vince Anderson and Andreas Behm) have really helped me with that. They’ve helped me break myself down and build myself back up. I wasn’t a horrible hurdler when I first got to college, but I was far, far away from where I am now. That title I had in high school didn’t mean anything. I knew it was going to be harder ‘cause when I practiced over 42’s in high school, I didn’t know how I was gonna do it in college. I was like, ‘Man, I gotta get in the weight room. How am I gonna do this?’ My coaches here have set a more basic foundation. A lot of basic beginner stuff that I wasn’t focused on because I was trying to pick up where I had left off in high school. Those technical things we talked about in high school I can come back to now. Like the angle of the lead arm, stuff like that, how you lean into the hurdle, the timing of the lean. Overall I’m just more knowledgeable now. Not just about technique, but about nutrition, weightlifting. It’s a totally different game.”

In the past few years at A&M, Davis has packed on pounds of muscle, has maintained a healthy diet, and has increased his sprinting speed. While various injuries have limited him at times and led to some setbacks, the adjustments he has made to competing at the collegiate level have been paying off. In 2012, he finished 2nd in the NCAA final to Andrew Riley of Illinois. With a -3.5 wind blowing in their face, Riley finished in 13.53 to Davis’ 13.60, while Spencer Adams of Clemson finished third in 13.73. Davis had entered the final with the fastest semi-final time. Again, being smaller, the stiff headwind had a greater negative effect than it did on Riley. In the semis, Davis ran 13.26 with a slightly illegal tailwind of +2.2, but never came close to finding the same rhythm and cadence in the final.

In May of 2013, Davis won the NCAA West Regional race with a 13.27, but again the wind was slightly illegal, this one being +2.1. At the NCAA national championships, he hit the first hurdle and briefly lost balance before accelerating and dominating the race, winning in 13.14. Eddie Lovett of Florida finished second in 13.32 while Adams came in third in 13.34. The +3.5 wind for this race was very illegal, so while the victory was sweet, the fact that his legal personal best was still the 13.37 that he had run in 2012 at the Big Twelve Championships remained a source of frustration.

Davis feels that the 13.27 he ran at regionals best represents where he is right now. “It just felt so easy. It felt sloppy, but I was locked in. No mistakes were made in that race. In that NCAA [nationals] race, I made two mistakes. I should’ve run 13.0 in that race. When I got over the first hurdle, I didn’t use my lead leg enough, so when my trail leg came down, I veered to the left and lost balance. I hit that first hurdle too, which is something I’d been focusing on not doing at all since the Olympics.” (In the 2012 Olympics, Davis hit the first hurdle hard in his semi-final heat, effectively ruining his chances of qualifying for the final). “That too could’ve been the cause of why I veered to the left. Hurdlers veer because one leg is more powerful than the other. After that first hurdle I started focusing on putting a decent amount of force into the ground with both legs. That 13.14, in order to hit that time again without wind, I’d have to get a little bit stronger. And I need to be injury-free.”

Davis celebrates his 2013 NCAA victory. (photo courtesy of galleries.ncaa.com)

Running with the Big Dogs

At the World Championships that took place this past August in Moscow, Davis once again fell short of qualifying for the final at a major international championship. So he finds himself in a similar position that he found himself at the end of his high school career. His accomplishments as a collegian don’t mean a thing to the David Olivers, Ryan Wilsons, or Jason Richardsons of the world. Same thing for world record holder and occasional training partner Aries Merritt. At this level, Davis must prove himself all over again.

In the preliminaries in Moscow, Davis was lined up next to US national champion Wilson. While Wilson finished in 13.37 to Davis’ 13.38, it was quite obvious that Davis was working a lot harder to run that fast. After the race, Wilson said that the race felt easy, like “a jog in the park,” and that he just wanted to make sure “Wayne didn’t pass me.”

In the semis, Davis was surrounded by older, bigger, stronger hurdlers. “That was the most stacked race I’ve ever been in in my life,” he recalled. All three eventual medalists – Oliver, Wilson, and Sergey Shubenkov of Russia – were in the heat, not to mention Riley (who competes internationally for Jamaica), William Sharman of England, and Artur Noga of Poland. Davis got out very well and was leading after four hurdles. But then the flood came. A wave of hurdlers surged past him, and he fought to hold on to seventh place in a decent 13.47.

Davis had been dealing with a nagging hamstring strain heading into the meet, and his training had suffered as a result, which at least somewhat explains his late-race fade. “I wasn’t feeling like myself,” he said. “The hamstring had been bothering me for a while, ever since NCAA’s. I was constantly tweaking it. In the preliminaries I felt something in my hamstring. I went in praying I wouldn’t pull up in the middle of the race like [Dayron] Robles.” (Robles, the 2008 Olympic Champion, pulled up lame with a hamstring pull in the finals of the 2012 Olympic Games). “I felt better the next day, for the semis, but I think I burned myself out. I hadn’t been training. I forgot that flow. If you haven’t been training and you try to keep the flow, it’s not gonna work. Those guys are so seasoned and they’re so sharp at that moment, they know what they’re doing. I wasn’t at that point.”

Davis battles eventual 2013 world champion David Oliver in the semi-final round. (photo courtesy of www.zimbio.com)

So what must Davis do to reach that next level? A lot, he concedes. Much of it mental, much of it physical. “To run with the big dogs, I just have to figure out the mental game. I need to stay at a mental state where I’m always in a high competition mode, regardless of the meet. Always be ready, like my coach said. I feel like once I can master that, then that’s when I’m gonna start to be more consistent.”

At the World Championships, Davis felt as burned out emotionally as he did physically. A playful individual by nature, he feels that being too serious for too long heading into a meet takes him out of that optimal competitive zone. “When I’m doing my warm-up and going over hurdles, I’ll be playing around. But as soon as we get in the check-in area, at that point, my mind is only on what I’m going to do. Playing around when warming up keeps me from getting emotionally burned out. I don’t like to be in that focused state too long. That’s what happened at the at the World Championships. I was constantly visualizing my race. By the time I got to the race, all the emotional energy had been spent visualizing. So there has to be a limit to how long you can focus, and you have to know what your limit is.”

As for the physical side of things, he needs to figure out a way to keep the injury bug away. “I have to be more proactive in preventing them. I have to stretch more often. The injuries are coming ‘cause my hips are tight. I used to be able to do side splits and front splits, and I can’t do those anymore. And the hurdles are higher.”

Davis identifies his hip flexors and ankles – “minor” muscles that are very important to a hurdler’s success – as the two main areas where he needs to get stronger. The ankle that he sprained prior to indoor nationals in high school still gives him problems “to this day. I re-sprain it all the time because it’s still loose and weak. Who would know that something stupid you do in high school can still bother you? I recently went to a sports scientist who’s had me doing exercises to tighten up the ligaments within my ankle. Not only will that improve my rebound when I hit the ground, but I’ll also be quicker between the hurdles because my ankles aren’t gonna give as much when I run.”

A Student of the Sport

Throughout his life, Davis has been one who seeks out the wisdom of those who are willing to share it. He has developed relationships with many sprint coaches, hurdle coaches, sprinters, hurdlers, former hurdlers, and former sprinters who have provided him with insights on what it takes to excel. Davis puts former US record holder Dominique Arnold at the top of the list of those who have mentored him. He and Arnold talk over the phone two or three times a month, and they conversed even more frequently in the months leading up to the World Championships.

“You can just tell he’s a student of the sport,” Davis said in reference to Arnold. “He talks to me about everything. Lead leg, trail leg, nutrition, weights, what to do when you’re in a slump. He’s like a life coach in a way. He’s been the most complete person in terms of helping me out as an athlete. When I ran 13.14, he said when you run fast your hips are gonna start popping, and he was exactly right. He said that’s why people’s bodies fall apart at high speeds. He said your body can’t handle the speed of the rotations. You have to strengthen your hips to get used to going that fast. If your hips are popping at 13.1, you have to strengthen your hips.”

Early in Davis’ collegiate career, he received a piece of advice from Allen Johnson that has remained useful ever since. “I asked him how he gets over the hurdles so fast, and he said you have to commit to the hurdle. Everything you’ve got, you have to put it into the hurdle. Don’t go crazy and be wild with your arms. Keep it controlled. But don’t hesitate. When you have any hesitation, the hurdle wins. It’s another way of saying ‘attack the hurdle.’ At times you get so focused on technique that you forget that hurdling is an aggressive thing. I definitely forgot that when I started going over 42’s. Hearing him say that got my mindset back where it needed to be.”

Davis also mentions David Payne, David Oliver, and Oliver’s coach Brooks Johnson as others who have gone out of their way to offer advice. After the semi-final race at the World Championships, Johnson explained to Davis what he was doing wrong with his trail leg. “I wish he had told me before the race,” Davis said, only half-joking.

On occasion, Davis gets to train with former Texas A&M Aggie and current world record holder Aries Merritt, who stomped all over the world in 2012. Though Merritt’s 2013 hasn’t been nearly as spectacular, he is still, in the eyes of Davis, a valuable resource and a treasured training partner.

“I don’t train with him that often,” Davis said, explaining that Merritt usually trains in the morning, whereas the team practices in the afternoon, “but all my focus is on him when he’s here. Just trying to pick up on what he’s doing – his rhythm, his mechanics. I’m always comparing myself to him. Why is he fast? Why is he faster than me? What is he doing in his technique that I’m not doing? Is he stronger than me or more efficient than me?” Davis notes that Merritt’s strengths include “his economy of motion. In between the hurdles is where he really sets himself apart in terms of economy of motion. His feet barely leave the ground, but each step he takes is powerful. Overall he’s just a kick-ass hurdler.”

Staying Humble

Now that Davis has achieved a significant level of success in the hurdles, he often finds that he is the one who is being looked up to by younger athletes. When youngsters ask him what they need to do to get better, he tells them, “You’ll get out of it exactly what you put into it. Spend hours studying your event, every dimension – not just technique, or strength, but everything – nutrition – don’t skimp on one thing. Have the whole circumference of things. Even though you might not be the best in sprinting or strength, you’ll become a better well-rounded athlete by getting a little bit better at each part.”

The success he has achieved up to this point has not made him feel self-satisfied. Instead, it fuels his hunger to achieve more, because he realizes there is so much more to do. “I’m no Bolt,” he said. “I’m no Oliver, no Liu, no Robles. And since I’m the guy who likes to chase records, I see myself so far way from the [world] record, I can’t be cocky. There are people out there who are beating me. So I can’t be satisfied until I break the world record, until I’m the best who ever walked the earth. You have to be humble under the people who have been better than you. Even once you break the record, you have to do it again and again. Look at Nehemiah. He broke it three times. 13.16, 13.00, 12.93. Now that’s a legend. How can you be cocky when you look at a guy like that?”

And so for Wayne Davis II, the chase continues. To the next workout, the next weight room session, the next race. It is a chase that never ends.