Timing at Touchdown

In the previous two issues of The Hurdle Magazine, I have discussed the timing aspect of hurdling in regards to take-off, and then in regards to positioning on top of the hurdle. In this article I will conclude this series by discussing timing at touchdown off the hurdle.

[am4show not_have=”g5;”]

[/am4show][am4guest]

[/am4guest][am4show have=”g5;”]

First, understand that timing at touchdown can only be on point if it has already been on point at take-off and on top. The mistake a lot of hurdlers make is that they get lazy during descent. Or maybe lazy isn’t the best way to put it. Maybe it would be more accurate to say that they focus so much on getting to the next hurdle that they forget to finish the action of clearing this one. Experienced hurdlers who have ingrained their technique can kind of go on pure instinct, but even experienced hurdlers can get so caught up in racing that they can be susceptible to errors during touchdown.

Let me go ahead and explain how you want things to occur, while also pointing out mistakes that you want to avoid.

Lead Leg:

At take-off, the knee of the lead leg drove upward and attacked the crossbar. On top of the hurdle, the leg extended, on a slightly downward angle, with the knee slightly bent. Now, upon descent, the lead leg will cycle back to the ground in a rotary motion. Throughout the action, the toes remain pointing up, with the ankle flexed. In this part of the motion, the heel drives back under the hip so that the foot lands directly in line with the hip, with the ball of the foot contacting the ground. From this position, the hurdler can immediately sprint off the hurdle in a seamlessly continuous flow.

The mistake a lot of hurdlers make – a subtle but significant one – is that they don’t “finish at the bottom,” as I like to put it. When the foot is maybe six inches away from touchdown, the hurdler will stop driving the foot back to the track, and will let it drop on its own. Therefore, there’s no pull-back with the foot. The foot lands slightly in front of the hip instead of under it. In effect, the hurdler is putting on the brakes. So instead of a seamless return to sprinting on the ground, there will be a slight pause when the foot touches down (until the hips move back in front of the foot), causing a slight loss of speed, which causes the need to re-accelerate. The athlete therefore ends up working a lot harder than he or she needs to over the course of a 10-hurdle race, making him or her more prone to late-race breakdowns.

Trail Leg:

At take-off, the trail leg pushed off the ground. On top of the hurdle, the trail leg raised upward/forward into position. Now, upon descent, the knee of the trail leg continues to raise upward in a tight motion, with the heel staying close under the hamstring so that the knee continues to lead the way, not the foot. In terms of timing, the trail leg knee will be directly facing the next hurdle at the exact moment when the foot of the lead leg touches down. The knee should be high – at least waist high, preferably chest high, ready to apply thunderous force to the track on the next stride.

If the trail leg knee reaches the front too soon – which is not a common problem, but it does happen – then there will be a pause in the trail leg, as it waits for the lead leg to land. The first stride off the hurdle will kind of plop down because the hips stopped moving when the trail leg stopped moving.

The more common problem is that of the heel of the trail leg getting away from the hamstring, causing a wider, longer path to the front, and also causing the foot to lead the way instead of the knee. When this occurs, the hurdler loses control of the leg, and anything bad can happen – smacking the hurdle with the ankle or knee is the most likely result. Even if you don’t hit the hurdle, the leg won’t make it all the way to the front, the knee will be low and to the side, and the foot will drop to the ground, wasting the first stride off the hurdle. That stride will have no force in it, and it won’t cover any ground. So the next two strides will require much more work in order to get to the next hurdle in rhythm, at the optimal take-off distance.

Here, as Sally Pearson descends, she keeps the heel of her trail leg tucked in close to her hamstring, and she keeps her knee facing the front so that the knee can lead the way.

Lead Arm:

At take-off, the lead arm rose up to about the height of the nose or cheek, or forehead at the highest, with the elbow bent. On top of the hurdle, the lead arm began opened by extending forward with the lead leg, remaining slightly bent, and opening outwardly slightly at the elbow in order to give the trail leg room to come through. Now, upon descent, the lead arm continues to cycle downward, pulling back until it reaches the back pocket. So the lead arm basically mimics the action of the lead leg (or vice versa, depending on how you look at it).

The pull-back motion at the bottom, which coincides with the lead leg heel pulling back under the hip, serves the same purpose – it helps to put your body at an angle where the chest is in front of the hips and the hips are over the foot, enabling you to move forward in a continuous, seamless, fluid motion, with no pause upon touchdown.

So, at touchdown, the lead leg foot is under the hip, the trail leg knee is facing the next hurdle, and the hand of the lead arm is on the back pocket.

Any mistakes with the lead arm upon descent and touchdown are going to be continuations of mistakes made prior to then. If the arm swung across the body upon take-off, it’s going to swing across the other way upon descent. The swinging motion will cause the hips to twist, and you will land off balance.

Trail Arm:

At take-off, the trail arm stayed bent, with the hand driving back to the back pocket. On top of the hurdle, it stayed in that position. Now, upon descent, it punches back up. In effect, it switches places with the lead arm, completing the running-over-the-hurdle action.

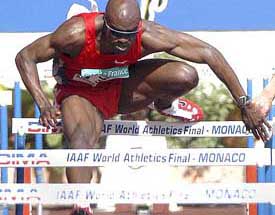

Here, Allen Johnson demonstrates impeccable positioning of both the lead arm and the trail arm as he descends off the hurdle.

Hips:

Upon descent, the hips do what they do throughout the entire race: push forward. As mentioned above, if the hips are twisted upon landing, it’s not because of the hips, but because of the arms swinging. If the hips are in fact the cause, then the mistake occurred earlier. In most cases, the issue is that the hips twist during the last step before take-off, as the hurdle prepares to attack the hurdle instead of running through the hurdle.

Here, both Dayron Robles and Anwar have a slight twist in the hips upon landing, but for athletes of this caliber, it’s a minimal mistake due to their superior speed and strength.

Lean:

As I always tell my hurdlers, it is so important to hold the lean upon touchdown. Just like the hips keep pushing forward, the torso must also keep pushing forward. Many hurdlers do everything right throughout hurdle clearance and then ruin it all by standing straight up when they touch down. All that forward momentum is now going upward. Terrence Trammell was the best hurdler I’ve ever seen when it comes to holding the lean, especially in the early part of the race.

So that’s a wrap! Hope you’ve enjoyed the “Timing” series of articles over the past three months, and that they’ve helped you to understand how timing is an integral aspect of executing technique effectively.

[/am4show]